Berkeley may ban plants close to buildings in top wildfire zones

UPDATE: Council approved the item unanimously at its special meeting Tuesday. Stay tuned for ongoing updates.

A bold plan to tighten wildfire prevention measures in Berkeley's most vulnerable neighborhoods heads to the City Council this afternoon.

At a special meeting Tuesday, officials will consider changing city fire code to require stricter defensible space in Berkeley's highest wildfire hazard zone.

The move is part of a larger Berkeley Fire plan — called EMBER, for "Effective Mitigations for Berkeley’s Ember Resilience" — to ramp up wildfire preparedness.

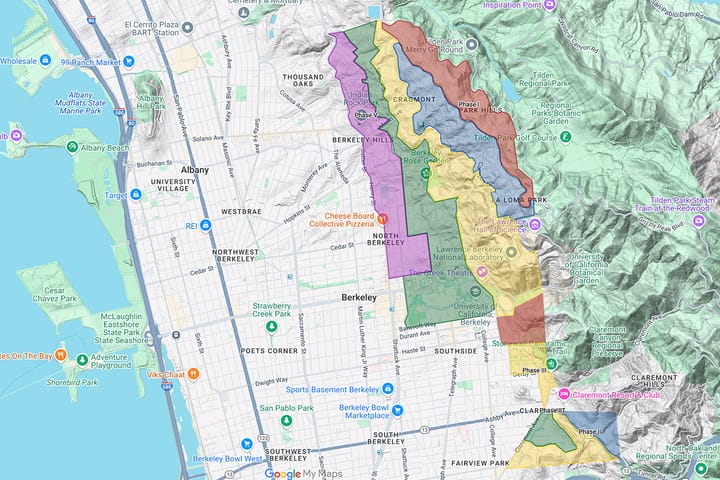

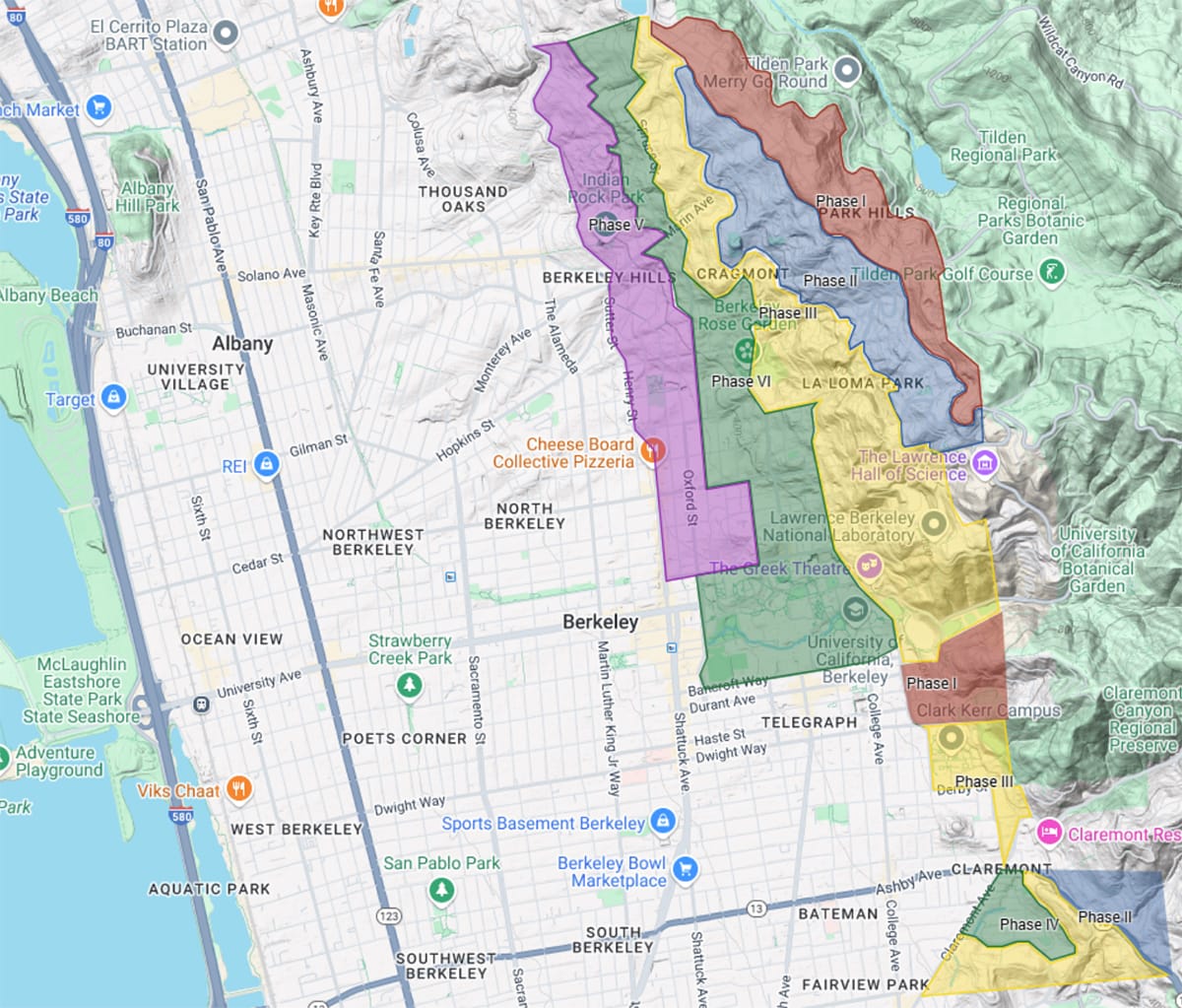

The proposed changes rest on updating the city's wildfire hazard map, which is also on Tuesday's council agenda.

Maps determine which properties would be required to do work to mitigate wildfire, such as trimming, cutting and mowing to create "defensible space" around structures.

Defensible space is intended to slow fire and give fire crews room to maneuver.

EMBER has a few components, but the biggest change is requiring a strict ember-resistant area, or "Zone 0" in defensible space-speak, from the base of structures out 5 feet in the city's highest wildfire hazard zones.

Under BFD's proposal, no vegetation would be allowed in Zone 0 (pronounced "zone zero").

Houses in Berkeley's Park Hills neighborhood, between Grizzly Peak Boulevard and Tilden Park, would be required to remove plants from the base of the building out 5 feet under the proposed Zone 0. Wood fencing would need to have 5 feet of space or be made of noncombustible material against structures. Kate Darby Rauch

Hardscape, such as gravel or rocks, or plain dirt, are the recommended alternatives. Plants in noncombustible pots would be allowed, with some height restrictions, as well as tree trunks or boles, as long as their leafy crowns clear roofs by 10 feet and aren't near chimneys.

Wood fencing would also be restricted in Zone 0, which means 5 feet of space or noncombustible fencing against structures, among other measures.

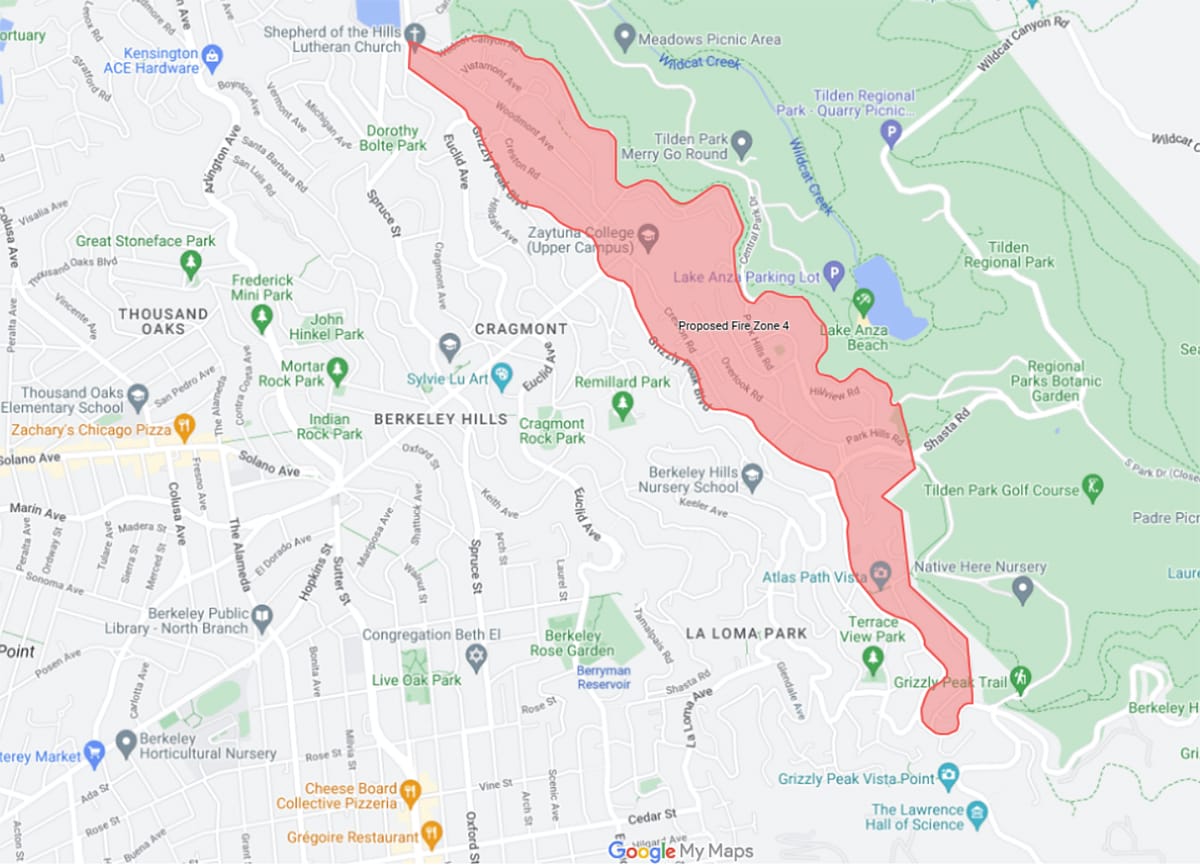

The proposed Zone 0, if adopted, would initially apply to just two areas of the Berkeley Hills: Panoramic Hill, above the UC Berkeley football stadium to the southeast, and a quarter-mile residential slice between Grizzly Peak Boulevard and Tilden Park.

"The most likely scenario for a wildfire of this magnitude to occur is from an ignition to the east of the city within Tilden or Wildcat Canyon Regional Parks."

"While a fire can ignite anywhere in the community, few locations within the built environment provide enough vegetative fuel to provide the 'runway' necessary for a wildfire to gain the size, speed and energy required to transition to a structure-to-structure conflagration. The most likely scenario for a wildfire of this magnitude to occur is from an ignition to the east of the city within Tilden or Wildcat Canyon Regional Parks," the fire department staff report found.

"Such an ignition, during a Diablo Wind event, has the potential to significantly impact the eastern edges of Berkeley. If the properties at Berkeley's eastern edge are not prepared to receive wildfire, they may facilitate a wildland fire's transition… that would burn west toward the Bay until the wind stops or changes direction."

In time, other "very high fire hazard" areas of the city would be subject to Zone 0, but the fire department says it is aiming for a phased approach.

"This will prioritize effective mitigations with limited resources. Focusing resources on the highest priority areas, creating a buffer along the edges of the community can prevent the transition of fire from vegetation to densely spaced structures, interrupting the initiation and propagation of urban conflagration in the built environment," the council report says.

Berkeley Zone 0 plan sparks debate

The Berkeley Fire Department introduced EMBER earlier this year, with neighborhood meetings, a City Council study session, and presentations to the city's Disaster and Fire Safety Commission and Public Safety Committee.

The concept has largely been met by positive response, said Berkeley Hills Councilman Brent Blackaby, who lives in a very high fire hazard area, supports the plan and acknowledges the work it will take property owners.

But vocal opposition has been escalating, especially to the strict Zone 0. Some took to social media in advance of Tuesday's vote.

"My main concern with the council voting for this draconian EMBER plan, is that it will be so difficult — and largely unnecessary — for residents to comply," Nenelle Bunnin told The Scanner. Bunnin lives in a neighborhood that would be subject to the change.

"It appears that they are not taking into account all of the research showing which plants and trees are not flammable, and in fact in some cases are protective during a fire," she said.

Another opponent, Rhonda Gruska, who's been leading the social media opposition, also challenges whether the fire department has done sufficient research.

Gruska said she rents in high hazard areas in a potential Zone 0 area.

"I wish the fire department would focus on inspections of structures, as opposed to targeting plants," she told The Scanner. "I have removed the juniper that was growing here. No problem. And I understand that an oleander in the front yard is supposed to be full of volatile oils as well. But BFD has not mentioned it."

She adds: "I appreciate the annual inspections, as that is the only way I can get the landlords to take care of keeping this huge yard with many plants under some semblance of control, as I do not have the equipment or time to do it all myself."

One social media poster bemoaned the loss of pollinator habitat under the city's proposal. In reply, someone said her yard provides great plants for pollinators, just 5 feet from her house.

"We're trying to stop ember storms."

Councilman Blackaby, however, said he has faith in the science behind the EMBER proposal.

"While there is always the opportunity for additional research, we are confident that the testing done by the National Institute of Standards and Technology and the Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety, as well as post-fire analysis conducted by Cal Fire, supports the importance of Zone 0 mitigation to prevent wildland-initiated urban fires such as those which occurred in our area in 1923 and 1991," Blackaby said.

Creating a strict Zone 0 along Berkeley's border with wildlands can help protect the rest of the city, he said.

"Once whole blocks are on fire, and that fire blows into surrounding structures on nearby blocks, then sure, Zone 0 is less useful," he said. "But we're trying to stop ember storms — being cast from wildland areas — from igniting structures and becoming exponentially more dangerous. That's where Zone 0 is really valuable," he said.

In addition to Zone 0, the EMBER plan calls for education and incentives for homeowners to "harden" their homes against fire, measures such as Class A non-combustible roofing, double-pane windows, ember-resistant vents, gutter guards and non-combustible exterior siding.

It's the combination of defensible space and hardening that bring maximum protection from fire, the Berkeley Fire Department says.

"Frankly, home hardening and defensible space are two peas in a pod. Both are really important to preventing ember storms from metastasizing into structure-to-structure conflagrations," Blackaby said.

State law already requires new construction in high wildfire zones to adhere to strict fire codes with many of these measures. This includes large remodels and ADUs or in-law units.

But Berkeley is largely built-up, and new construction is rare. The city can't legally require hardening on existing homes.

State advances Zone 0 to lively debate

The local Zone 0 debate parallels what's happening throughout California, as the state Board of Forestry and Fire Protection moves to finalize Zone 0 rules, setting the end of year as its target.

In 2020, the legislature passed a law requiring Zone 0, directing the board to come up with the details as it's charged, such as what will and won't be allowed in the area. The process, initially expected to take a year or so, dragged on, a testament to the challenge of trying to reach consensus on one law for a large state that will mean significant landscaping changes for some people.

After January's destructive Los Angeles fires, Gov. Gavin Newsom demanded the board finish the Zone 0 job. The law can't be enforced without details, though many fire agencies, including Berkeley, have encouraged it for years.

The state's most recent Zone 0 draft, still under discussion, is similar to Berkeley's, calling for no ground plantings in the area. It also modifies rules for the next area, Zone 1, allowing fewer plants.

As per the draft, state law would apply to new buildings as soon as it’s finalized, but existing properties would have three years to comply.

The state sets the minimum wildfire regulations, including defensible space rules for all California high hazard areas, via Cal Fire, its fire agency.

Local jurisdictions such as Berkeley can enact stricter requirements. But they can't go weaker than the state.

Earlier this year, Berkeley Fire began working on its own Zone 0 regulations as part of EMBER. This was hastened by the deadly and destructive Los Angeles fires, Berkeley Fire Chief David Sprague said.

At a packed board of forestry statewide workshop on Zone 0 last week, one of many held over the years with similar often heated discussion, a mix of views were presented from "get on with it" strong support for the strictest approach, forbidding any plants in the zone, to passionate skeptics, calling for more study on options and impacts.

"The point is there shouldn't not be a Zone 0; it's how much vegetation," said Travis Longcore, a UCLA ecologist active in the state debate and often cited by opponents to strict requirements.

Longcore, who lives in a high wildfire hazard zone, accepts that the state is moving forward with some version of the law.

"I'm not addressing that. The question is what do the regulations look like. The research does not provide any scientific evidence that you should say there should be no vegetation in Zone 0," he told The Scanner, adding that he's reviewed research on the issue, but hasn't done any studies himself.

Some plant species are less flammable than others; some moisture-rich trees and bushes may even extinguish embers, he said. Longcore also calls for environmental review of strict Zone 0 effects before finalizing the law, echoing others at the meeting.

For no plants, he said, "You need to have really solid research backing that up, and need to investigate the alternatives equally well that will cost people less."

Others disagree.

Notably, scientists at the Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety, which is supported by insurers, and studies ways to protect properties from all kinds of disasters.

The institute has aggressively advocated for hardscape around structures in high fire hazard areas for years, including at California board of forestry meetings, citing its research and testing in outdoor lab settings and simulations.

The institute, which makes other recommendations for protecting buildings from wildfire, says blowing embers gather at the base of structures, including beneath attached decks, where they can set plants on fire and produce radiant heat, which then ignites buildings.

It considers this a primary way buildings erupt from wildfire.

"Eliminating fuels from the immediate area surrounding the building… can decrease ignition potential by reducing the possibility of a direct flame contact and radiant heat exposure to the building," the institute says on its website.

The institute's stance, agreed to by many experts, is that a watered-down Zone 0 greatly reduces the benefit, and can be confusing for property owners, not to mention challenging to enforce.

Berkeley Fire, as with many fire agencies, aligns with the institute's research and recommendations.

Longcore, however, says the institute's studies aren't peer-reviewed and published in journals, as with the gold standard of academic research.

The institute says its conclusions are "science-backed."

(The Scanner has asked the institute for a response, but hadn't heard back as of this week.)

Zone 0 buzz in Berkeley and at the state level share many of the same pro-con talking points.

Some Berkeley opponents to a strict Zone 0 standard cite a 2018 paper by Alexandra Syphard, a research scientist at the Oregon-based Conservation Biology Institute, that looks at factors leading to structure loss in wildfire.

The paper, which reviewed California fires between 2013-18, concluded that home hardening made more of a difference in protecting buildings than the length of defensible space.

"Zone Zero requirements are one of the most important things residents can do to protect their property from wildfire."

In an email circulating among Bay Area fire agencies, Syphard said she thinks some people opposing Zone 0 are misinterpreting her findings.

"I am sorry to learn that my work is being somewhat misrepresented in a way that could make residents more at risk to wildfire," Syphard wrote retired Orinda-Moraga Fire Chief Dave Winnacker, in a message shared with The Scanner.

"The study in which I recommend that excessive defensible space may not be needed is specifically talking about those who want to far exceed the 100' minimum, or those who want to moonscape their property and thus invite excessive colonization by un-irrigated invasive annuals (a concern most relevant to southern CA)," she wrote.

"My study found significant benefits of defensible space, particularly the closer you are to the structure. It is my thought that the Zone Zero requirements are one of the most important things residents can do to protect their property from wildfire.

"Studies that show a relatively larger effect of construction materials should not be taken to mean that defensible space should not be done or that it will not have benefits. This is particularly the case for Zone Zero, but it is also important to maintain 100 feet of appropriate defensible space (i.e., according to Cal Fire guidelines) for firefighter safety and maneuverability."

Syphard didn't weigh in on Zone 0 specifics.

Wildfire rules start with maps

Wildfire regulations, whether set by the state, counties or cities, are based on hazard severity maps. These maps delineate which properties are required to follow regulations.

Wildfire hazard mapping in California is complicated. The state, via Cal Fire, sets a mapping baseline.

As with defensible space laws, cities can expand but not reduce hazard zones based on local data. But first they must officially adopt the Cal Fire maps, which effectively means, we accept our responsibility to regulate these areas.

Berkeley Fire is aiming for expansion.

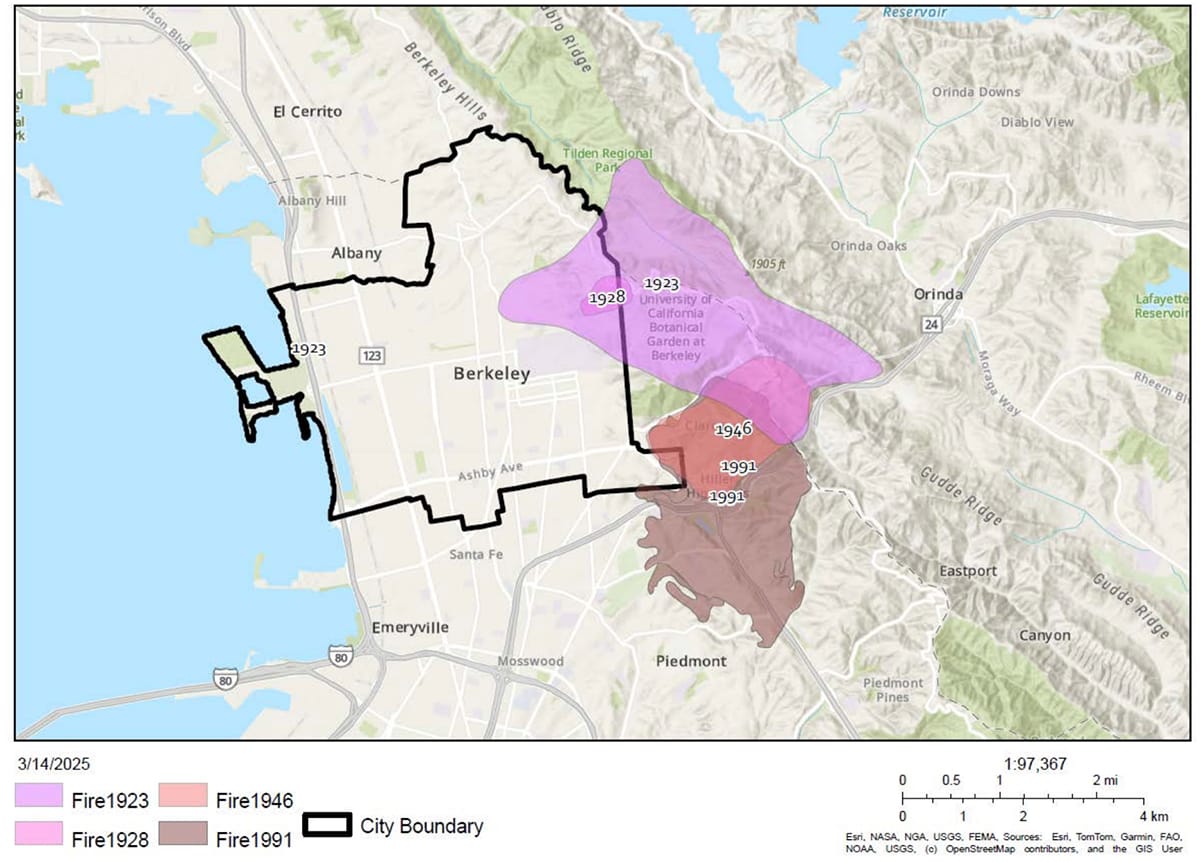

State wildfire hazard mapping, set in law, was prompted by the deadly 1991 Oakland-Berkeley firestorm, also called the Tunnel Fire, as a tool for guiding mitigation and prevention measures.

The mapping, GIS computer modeling, is based on numerous factors, including weather, topography, vegetation, smoldering embers and fire history.

Inputs are thrown into the model for the state to capture areas with the potential for experiencing a very high, high or moderate wildfire in a 30- to 50-year period.

Cal Fire maps these as wildfire severity zones.

Zone 0, under the current city and state proposals, would only be required in very high hazard areas. Other defensible space measures, extending out 100 feet from structures, are required in both high and very high zones.

These maps show the likelihood of wildfire, not its potential impacts.

This is an important distinction for fire agencies working on prevention, as the maps don't factor in variables such as housing density, housing materials or road dimensions — all of which can make fire more destructive.

"We don't have a comprehensive modeling tool for fire spread in the urban area," said Dave Sapsis, a wildland fire scientist and hazard mapper for Cal Fire. "With structures as fuel, we don't have a mechanistic model to understand urban conflagration."

Sapsis said the agency is working on adding structure-to-structure spread to its models.

The Los Angeles fires drove home the critical need for this, as wind-fueled spread between buildings is believed by most experts to be what made them so destructive and hard to contain.

"We're already in research mode trying to develop an operational tool that will provide characteristics of the urban environment, and capture the fire dynamics associated with structure fuels," Sapsis said.

In Berkeley, BFD Chief Sprague is also working to add structure spread to local mapping models.

To add to the complexity, Cal Fire produces two types of hazard severity maps.

One covers public land, such as regional parks and areas overseen by the U.S. Forest Service, where the state is the lead fire agency. UC Berkeley property falls into this bucket.

The other covers local responsibility areas: land governed by city and county fire agencies. These maps aim to identify developed areas most susceptible to wildfire spread from open space.

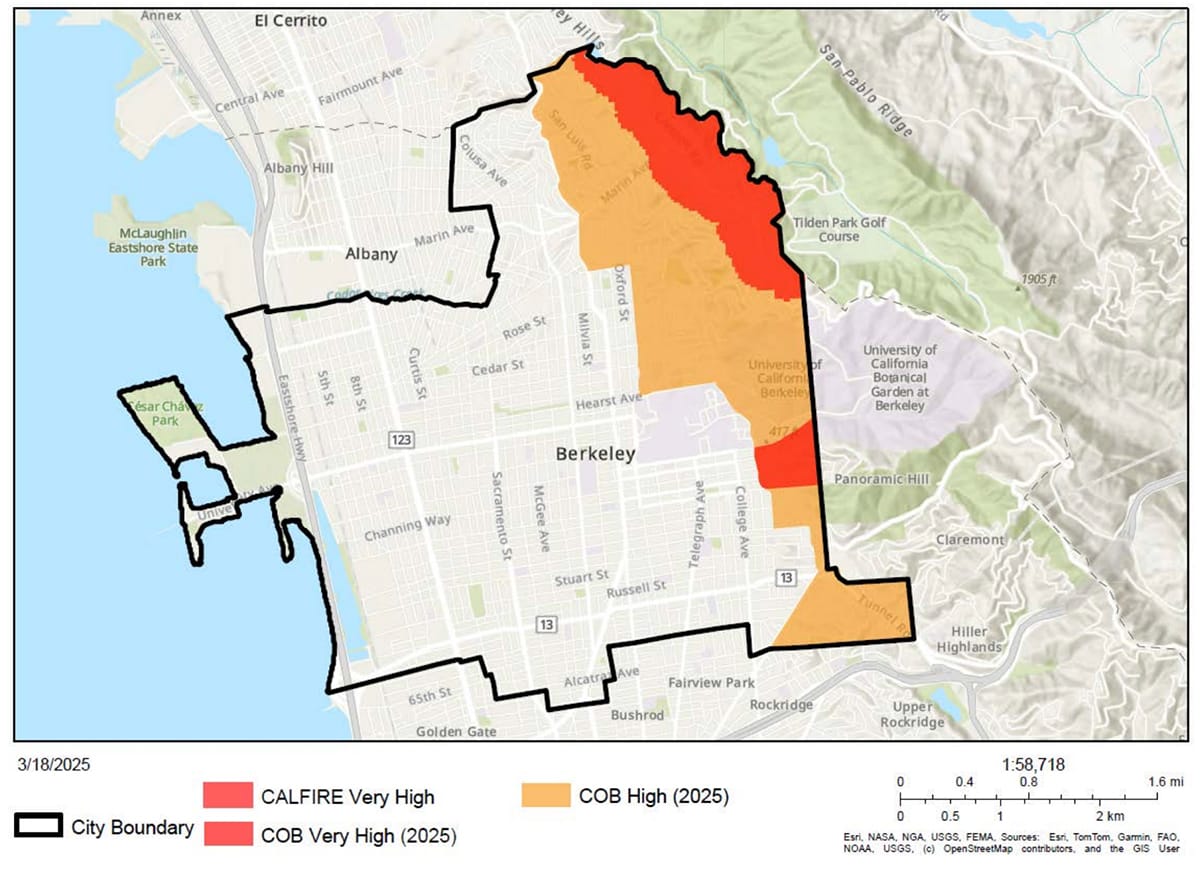

Both sets of hazard maps were updated recently for the first time since 2007.

In a surprise to many local fire agencies, including Berkeley Fire, high hazard zones across the urban East Bay hills shrunk in the updated maps.

The upper hills along the wildland urban interface (WUI), are still in the very high and high severity zones. But some parts of the lower hills shifted from "very high" to high or moderate, or were dropped completely.

Unlike Berkeley, however, fire hazard zones expanded elsewhere in the Bay Area. As a whole, the state increased its high and very high hazard areas by 168%.

Cal Fire's mapping tool lets you do a side-by-side comparison of the earlier and recent maps.

Sapsis said updates to the maps included the addition of local weather as well as hazard gradients. Earlier maps showed all hazard areas as very high. In the new version, some of these were kicked back to lesser hazard zones.

He said it's hard to say exactly why high hazard areas dropped across the inner East Bay, with so many variables at play.

One challenge, he said, is that the maps are based on probabilities, which may become less predictive in the years ahead: "The future has a lot of uncertainty."

Take the Altadena fire, he said, which leapt beyond the state's high hazard zones.

Carol Rice, a Bay Area-based ecologist and mapper who works with the city of Berkeley among other jurisdictions, said Southern California's frequent intense fire weather can lower Northern California hazards on the Cal Fire maps, as the model is based on relativity.

"The emphasis on burn probability and frequency of bad fire weather pushes the ranking of fire hazard severity to lower than we would expect in the East Bay because it’s relative to the whole state," she said. "Here we have fewer incidences of hot, dry weather. Since it's relative across the state, we don't show up as high."

But, Rice stresses, this doesn't mean the East Bay is at any less risk from fire. In fact, she said, history shows the opposite.

"[Cal Fire] focuses on frequency as an occurrence, and we don't have very frequent occurrences but, when they happen, they're a humdinger," she said. "We get those infrequent kinds of catastrophes."

Rice points to Berkeley's 1923 fire, and the 1991 Oakland-Berkeley firestorm as examples.

Augmenting the state maps with local variables is immensely helpful in understanding local vulnerabilities, Rice and Sapsis stress.

To this end, Berkeley Fire has asked the City Council to adopt the updated Cal Fire hazard map, as required by state law, and then expand the city's hazard areas beyond the state map in two areas.

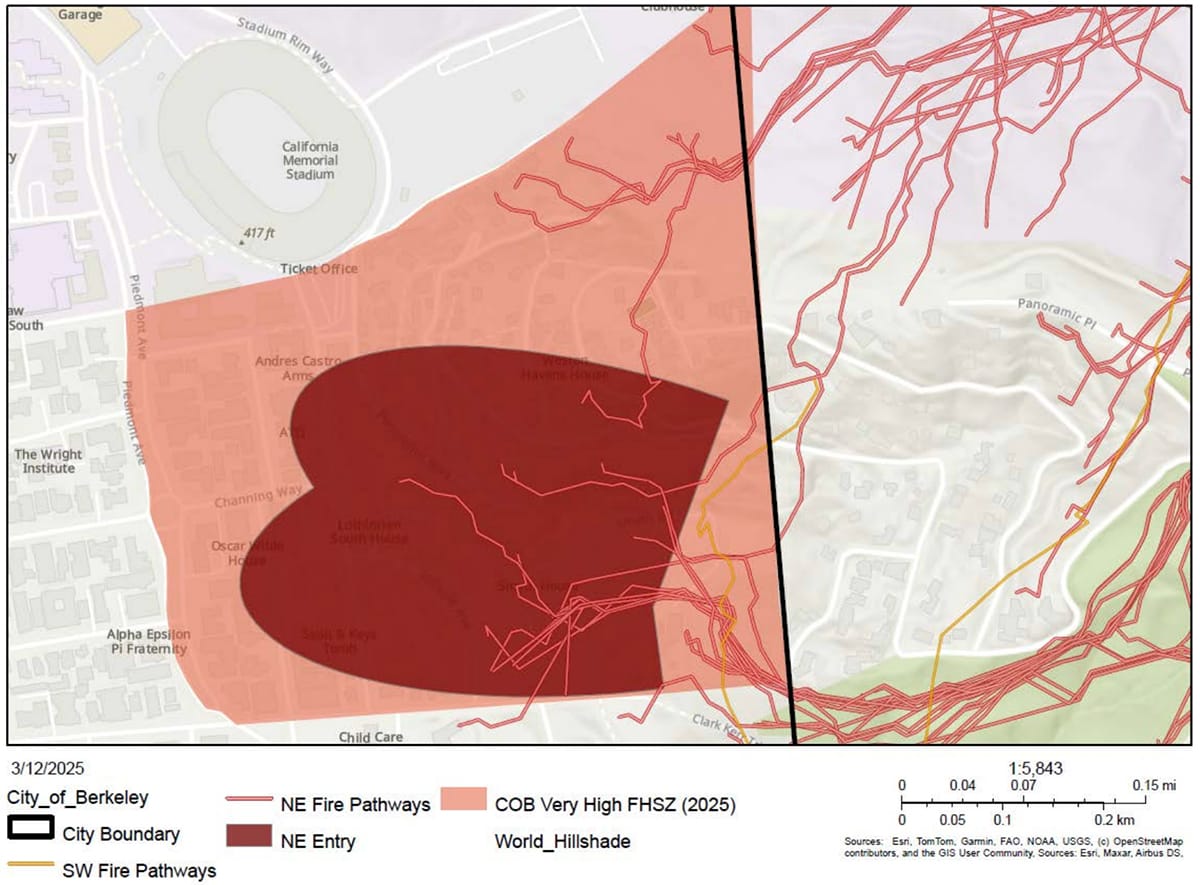

Specifically, the department wants to widen the very high fire zone around Panoramic Hill and extend the high fire zone westward down the hills. [See maps.]

The Grizzly Peak mitigation area is already covered by the state's very high fire hazard zone, so no local expansion is needed as far as Zone 0.

The Panoramic Hill expansion is based on BFD's own fire history analysis as well as fire pathway mapping, which identifies wildfire routes into the city, the department said.

If approved Tuesday night, Berkeley would modify its own wildfire hazard map, which currently has three zones.

The proposal calls for renaming the zones to mitigation areas — Flatlands (Zone 1), Hills (Zone 2) and Panoramic (Zone 3) — and adding a fourth called Grizzly Peak.

To help people understand the mapping requests, Berkeley Fire produced an interactive storyboard.

Updated city fire hazard maps would then set the stage for a phased enforcement and education focus, zone by zone, the department said.

"The resilience of an individual property only increases if done in conjunction with adjacent properties. Thus, successful implementation and enforcement will be more effective if concentrated in one region of the City at a time," the council report said.

Related coverage