Remembering Robert Shadric, a longtime Berkeley presence

To some, he was Robert. To others, he was Jamal. He often slept outside the Cheeseboard and could also be found on Euclid Avenue.

For a couple of weeks he was just a man found dead in a UC Berkeley bathroom on a chilly day in January.

Unidentified and, in coroner-speak, unclaimed, because they hadn’t yet found his family, his next of kin.

Many around Berkeley were asking questions, second guessing, curious and sad.

But this changed Thursday when the Alameda County coroner's office released the deceased man’s identity: Robert Eric Shadric, 52 years old, and transient.

On Jan. 9, Shadric's body was found in UC's Sutardja Dai Hall, at Hearst and Le Roy avenues, on the north side of campus. UCPD detectives said there were "no obvious signs of foul play."

The official identification comes as no surprise to many who knew Shadric, known to them as Robert or Jamal, depending on the moment, or maybe his mood.

Dots were being connected from the morning his body was found, comment to comment, report to report, from UC Berkeley maintenance staff to cafe and shop workers on Euclid Avenue near campus, to church friends, to the Cheeseboard on Shattuck Avenue in North Berkeley.

The man they knew as Robert or Jamal, or sometimes Jamil, was dead.

Shadric lived on the streets of Berkeley for at least 20 years, several people who knew him said.

He spent much of his time on Euclid Avenue near campus, and on Shattuck, in front of the Cheeseboard, and walking between the two neighborhoods.

Sometimes he stopped at Peet’s Coffee at Walnut and Vine streets. Sometimes, he sat in the sun in quiet spots on "Holy Hill," the campus of the Graduate Theological Union, now also used by UC Berkeley and a private high school.

Shadric was often quiet. Folding his blanket in the mornings. Eating his tuna on bread in the afternoons — no mayo, no mustard, just plain. Wire-frame glasses, sweatpants. Always neat and clean.

But he’d also preach, and could get ramped up and offensive.

"I started really talking to him 10 years ago," said Irma Perez, who works at The Campus Store on Euclid at Ridge Road. "He’s here every single day. Whenever he didn’t show up, we’d wait, we’d wonder."

And during the week of Jan. 9, Perez did just that.

"I was the only one working here that week," she said. Monday passed, then Tuesday, then Wednesday. No Robert.

On Thursday, she said, someone came in the store and shared that a man had been found dead in a campus bathroom. He was African American. He had dreadlocks.

Robert fit both.

"I instantly knew. In my blood," Perez said. "Because I hadn’t seen him. Rain, thunder, he would always show up."

She is still a little stunned.

Robert called her "Irmie," she said. His pet name for her. They joked, shared meals. He’d take the store’s sidewalk sign out in the mornings. Charge his phone inside. Keep his sandwich bread and tuna in the back.

He was super picky about food, she said, reading ingredients, paying attention to nutrition, telling her to do the same. He was a bit of a purist, she said.

He’d wait while she locked up the store on dark nights: "He made sure I was safe."

When a wiring issue caused a booming electrical explosion in the store a couple of years ago, zapping the power, she said, "I heard [Robert’s] voice, 'Irmie get out, Irmie get out.'"

He was very caring, she said.

And yes, he’d sometimes start preaching in front, a low ramble that could get loud, screechy, she said, and mean. Racist. Homophobic.

"I’d bang on the wall," she said.

She’d lecture him about being kind to everyone, pointing out the many who were kind to him.

Once she told him he was banned from the store for a month if he kept screaming.

"He listened. He stopped." At least for a while.

She never saw him act aggressive or violent, she said.

To Irma, he was always Robert. He often slept in front of the Cheeseboard, leaving in the mornings, sometimes circling back. There, he was known as Jamal.

This makes Chris Llave, another Campus Store worker, laugh.

Llave was close with Robert for more than 20 years, he said, starting when he used to work at Stuffed Inn, a popular Euclid Avenue sandwich shop that closed in 2023. Robert was a regular on the block.

"That was his AKA," Llave said of the name Jamal. "I always called him Robert."

Well, not always.

"Or Sprouty," Llave said. His pet name for Robert. "And he used to call me Spuddy — because he thought I had a potato head."

They talked. They teased. They did karaoke together, singing to tunes blasting from their phones. Robert’s favorites included "Stars," by Seeing Red, and "Wonderwall," from Oasis.

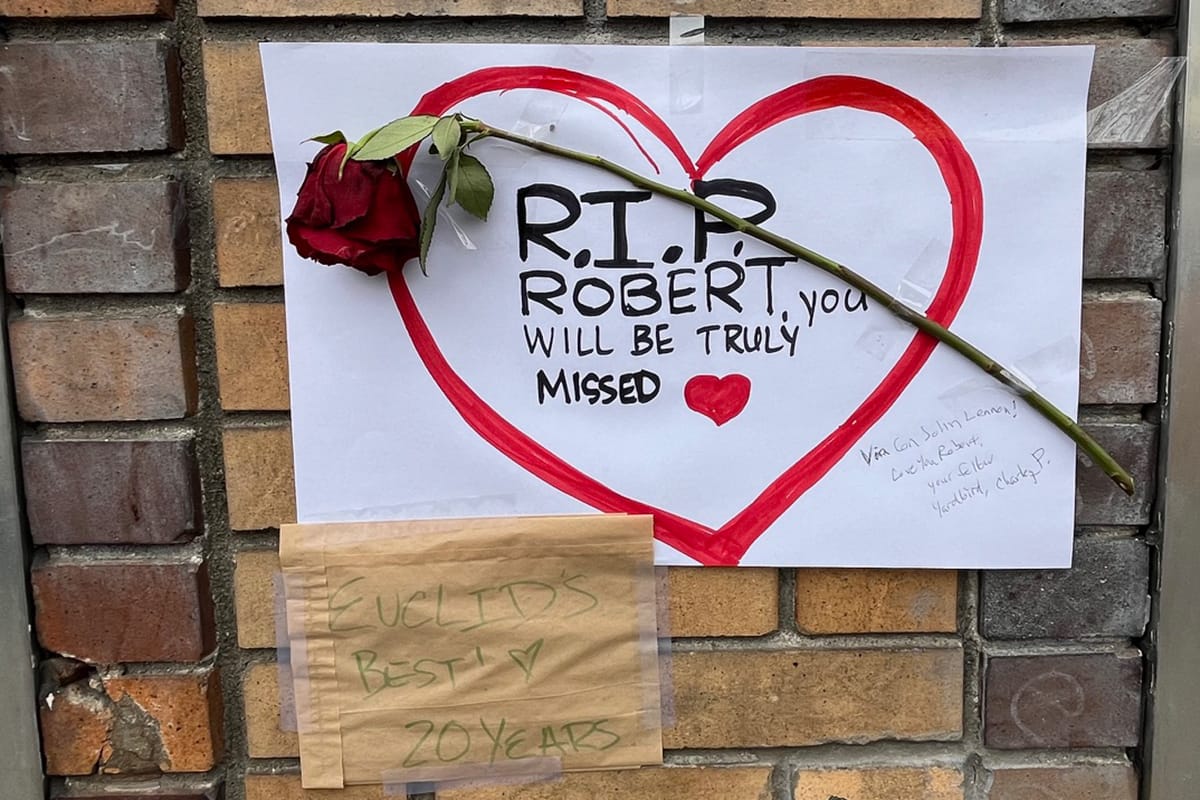

Shrines to Robert/Jamal went up outside The Campus Store and the Cheeseboard shortly after The Scanner broke the news that a man's body had been found on campus.

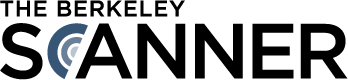

Robert Eric Shadric. SMCHS

Llave thinks Shadric grew up in Piedmont, but went to high school in Berkeley.

After publication, a reader shared Shadric's senior photograph from St. Mary's College High School in 1990.

He has a sister in the area who used to visit him on Euclid, Llave said. He’s worked at a Starbucks. He’s worked at McDonald’s.

Perez said she thinks the sister may live in Orinda, and his mother may be there too.

It’s hazy. (The Scanner will update this story if we learn more.)

Robert doesn’t like to talk about his past, they said. He gets upset and bitter.

Llave was on vacation in the Philippines visiting family over Christmas when his daughter called from the Bay Area to tell him she thought Robert had died.

"Part of me is in denial," Llave said recently. "I feel weird working today. This is my first day back. I spent every day with the guy."

"He could be a pain in the butt, but I saw a different side of him that was perfectly normal," Llave said.

Llave wasn’t wild about Robert’s preaching.

"You ain’t preaching. You’re bitching,” he said he told his friend. "I could be real hard on him and he took it; he never got mad at me."

"Don’t stomp on my blessing, Irmie"

A memorial to Robert Shadric at his usual spot on Euclid Avenue north of UC Berkeley. Kate Darby Rauch

Every Christmas, Robert gave Llave and Perez Christmas cards with gift cards — Amazon or Apple or Uber, they said.

"He never missed a Christmas," Llave said, pretty much since they met.

He also never missed her birthday, Perez said, giving her a card and gift. Always with a handwritten note.

"We knew the little kid," she said. "He was sweet, he was very caring."

When she tried to give back the cards or tell him not to spend his money that way, he’d tell Perez, "Don’t stomp on my blessing, Irmie."

Robert’s preaching or lecturing had religious tones, sometimes pierced with spite. It was often nonsensical. Yearnings, hopes, warnings, accusations, fears. It could disturb people listening.

Michael Drell, a seminarian in Berkeley’s Graduate Theological Union community, lives around the corner from The Campus Store, and knew Shadric from the sidewalk.

They shared an interest in religion and had deep conversations, Drell said. But they didn’t always agree.

One thing he appreciated about Shadric, he said, was that he could listen: "He’d calm down and debate with you; he wasn’t shouting in your face."

Shadric sometimes asked Drell to buy him snacks. Which he was always happy to do. His fussy rescue dog Rocco didn’t warm up to many people, but Shadric was one of them, Drell said. "He called him Scruffy."

Shadric would hang out by the All Souls Parish on Cedar Street, where Drell works. Sometimes he’d bring up a specific sermon, though Drell never saw him inside. He suspects Shadric was listening from outside.

Drell was in New York when Shadric died, and got a text from a colleague with the news. "I was gutted," he said.

Alan Bolind, a UC Berkeley lab inspector, who met Robert on Euclid in front of the former Brewed Awakening cafe decades ago used to take him to church Sunday mornings at Sanctuary Berkeley on Parker Street.

Bolind, who learned of Shadric’s death soon afterward from a chain of campus employees, picked up Robert at designated places and drove him to the Christian service. He’d been doing this for the past couple of years.

The Sunday before his body was found, and before Robert/Jamal went missing, Bolind did the usual routine. He went to church with Robert, as he knew him, and took him out for lunch afterward, as he sometimes did. This time it was to California Fish Grill in El Cerrito.

They had a particularly great conversation.

"It was one of the best conversations I’ve ever had with him. He was the most lucid. Noticeably more so," Bolind said. They delved into Robert becoming homeless. He blamed others, Bolind said, but also, "He had humility." Which Bolind felt was new.

A religious man, Bolind said, in his heart, his soul he feels Robert is OK now.

"It’s not the way I would have wanted it to be played out. But yeah," he said, "God’s taking care of him."

Postscript

On or around Tuesday, Jan. 7, this reporter, who takes frequent walks around North Berkeley and crossed paths with Robert/Jamal numerous times over the years, often marked by an exchange of nods, saw him slumped and shaking in front of the Cheeseboard bakery in the morning. One of his usual spots.

But this was unusual, as he usually packed up early and didn’t linger on the ground. The pizzeria-bakery was closed on winter break. I asked him how he was doing, saying he looked sick.

"I’ve been better," he replied, raising his head slightly before dropping it again. Feeling worried, and also helpless, I went to the nearby Andronico’s and bought some ibuprofen and orange juice, bringing them back to him.

I sensed — and understood — that taking food or medicine from a stranger wasn’t something he was likely to do. Still, I encouraged him. "You need to bring down your fever."

A Cheeseboard employee showed up and encouraged him similarly. Later, I learned, she and other employees also brought him fever reducer, which they don’t think he took. I also heard they called for a crisis team, which spent time with him.

I called 211 as I walked away from him, asking for advice, and was told no outreach was available that day. Whatever happened to Robert/Jamal, I know I’m not the only one haunted, pained by wishing I’d done more.

See related posts on Reddit, which include hundreds of community comments from the initial discovery of Robert's body to our story here on who he was.