With sexual misconduct case settled, what's next for BHS?

Former students who made allegations against teacher Matthew Bissell have asked BUSD to overhaul its approach to claims involving sexual misconduct.

At first glance, Berkeley Unified School District's recent $13.5 million settlement with nine former students accusing a high school teacher of more than a decade of unchecked sexual misconduct suggests a level of resolution. A hint of closure.

Perhaps even vindication.

For the accusers, as well as for others close to the case. Families. The school community.

For some, the relatively large sum implies district wrongdoing. Though in the settlement, reached in September, BUSD admitted no guilt, despite previously substantiating related claims when it did its own investigation.

"Concerns ranged from inappropriate comments regarding clothing worn by female students to alleged sexual battery (i.e., 'accidental' touching of female students' butts, hips and waists)," that investigation found. It called the teacher's conduct and comments "severe and pervasive."

In recent legal documents, BUSD called the settlement "a compromise of a disputed claim." District insurance covered the payout.

But to Rachel Phillips, the first of the students to sue the district in 2021 over how it handled her allegations about Berkeley High chemistry teacher Matthew Bissell, the most important outcome from the case remains to be seen.

That's for BUSD to overhaul its approach to claims of sexual misconduct.

Bissell, also named in the lawsuit, was quietly "released" by the district in 2021, a few months before the case was filed. The confidential agreement allowed him to keep teaching until the state revoked his credential in 2022, Phillips said.

In prior media statements, Bissell's lawyers have denied any wrongdoing. They failed to respond to requests for comment from The Scanner.

At the time of the settlement, Phillips, along with the other eight former students who alleged misconduct by Bissell, asked the district to implement several carefully chosen steps designed to improve its response to claims of sexual harassment and abuse.

The suggested reforms, sent to the district by Elana Jacobs, the attorney who ultimately represented all of the women, were outside the settlement and are nonbinding or can't be enforced.

The district has yet to respond, Jacobs said.

But the changes are deeply meaningful to the plaintiffs — primarily for the sake of future students who may be confused, scared or upset by a teacher or staff person's comment, look or touch, said Rachel Phillips, who is now 39 years old.

"For me, the whole settlement was never about the money. I didn't even know I had a case that would go this route," she said of the negotiated arrangement.

Phillips accused Bissell, who was also a coach, of sexually abusing and assaulting her throughout high school, even after she complained to school officials.

Now living outside Portland, Oregon, Phillips said she plans to give some of the money to the preschool where she teaches, a financially struggling school for struggling students.

"For most of the plaintiffs, that was the most important thing," she said, of the nonbinding requests. "They were talked about throughout the [process]."

"It's hard to come up with those," she added. "Why is it our job to fix their system?"

From pain, signs of change

Jasmina Viteskic, Berkeley Unified's Title IX coordinator, said she couldn't comment on the lawsuit or settlement, or the plaintiff requests.

But she provided details on ways the district is strengthening its response to sexual harassment, steps she said started in 2020.

Title IX is the 1972 federal law prohibiting gender-based discrimination, including harassment, in educational settings that get federal funding. It requires, among other things, that schools investigate complaints and educate students and employees about their rights and responsibilities.

Some of the district's actions mirror the plaintiffs' requests; others have not been addressed.

After reviewing Viteskic's response, shared by The Scanner, Phillips and Jacobs each expressed skepticism based on what they believe is the district's irresponsible history in handling sexual misconduct.

They welcome improvements, they said, but take a "proof in the pudding" view.

At least a few Berkeley High students and parents say they have begun to see positive change, and are holding out that this will stick.

The plaintiff's requests include:

- The purchase of case management software for the district's Title IX office to track and manage sexual harassment complaints

- Increased classroom presentations about how to report sexual misconduct to the school and/or police, and exactly how that process works

- Increased education on what is sexual harassment, through assemblies, announcements and other means

- A reporting hotline

- The use of the remaining money from the district insurance payout (around $1.5 million from a $15 million pot) for community outreach/childhood abuse protections once the statute of limitations is up for any BUSD student who may have been abused by Bissell (through approximately 2046)

Steps taken by the district to date, as identified by Viteskic, include:

- Hiring a full-time Title IX investigator to work alongside a full-time Title IX coordinator. [The law requires a coordinator but does not set hours. The law requires investigation, but not a staff investigator.]

- Offering designated Title IX coordinator office hours at Berkeley High. The coordinator serves all schools.

- Implementing Guardian case management software for all district complaints including sexual harassment

- Hanging classroom posters on how to report sexual harassment at Berkeley High and Berkeley Technology Academy as well as creating a Title IX virtual resource page and a BHS Title IX information page

- Hiring a new Title IX counselor tasked with providing tailored support to students who have experienced or are accused of engaging in sexual harm

- Training Title IX "Focal Point" administrators at the middle and high schools

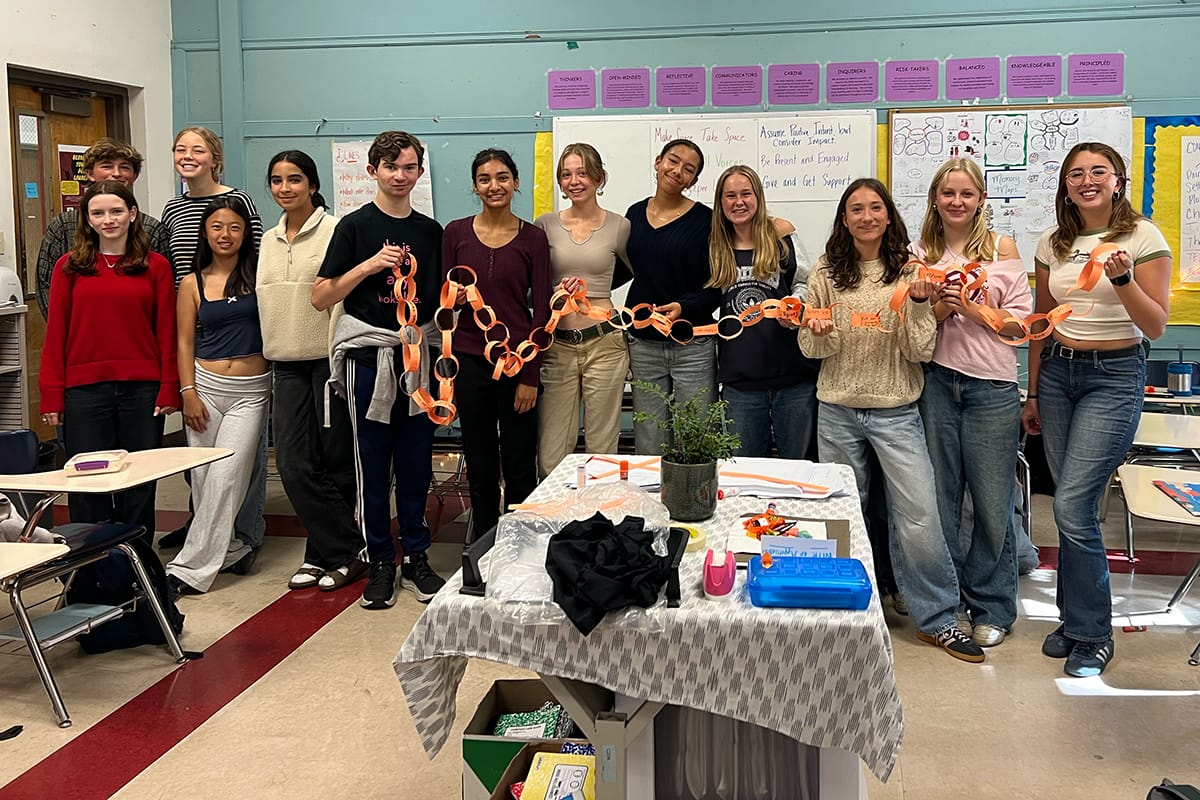

- Adding annual peer consent education in eighth grade that is provided by Berkeley High's Stop Harassing student group

- Creating a new "teacher on special assignment" role to provide annual consent education to all high school students

- Developing new district policy and staff training on how to maintain "appropriate adult-student interactions"

- Establishing the Superintendent's Gender Equity and Sexual Harassment Advisory Committee composed of staff, parents, community members and students

Viteskic attributed the district's actions squarely to students.

"Following our students' extensive advocacy efforts to improve the District's response to reported cases of sex based discrimination and harassment which culminated in the February 2020 student walkout, the District has undertaken extensive steps to ensure that all cases of sexual harassment are promptly addressed, investigated and our students are provided with adequate support," Viteskic said by email.

The student-led walkout in 2020 was to protest what they called Berkeley High School's "rape culture."

Organizers at the time pointed to the district's handling of the Bissell case, as well as other incidents, including bathroom graffiti that listed names of "boys 2 watch out 4," which students said was intended as a warning about sexual behavior.

"While the District notes progress since February of 2020, we recognize that ensuring our schools are free from sex based discrimination and harassment is an everyday objective and we remain committed to continued improvement in partnership with our students and community," Viteskic wrote.

Skepticism, hope after Berkeley High settlement

Elana Jacobs. Courtesy

In looking at the district's response, lawyer Jacobs was guarded in her optimism. And she had questions.

Of the Guardian database, she asked, "Is this program actually implemented? Who has access? Can you search by respondent name (i.e the accused)? Does it track formal Title IX complaints and informal? Verbal and written? Anonymous complaints?"

She asked why she hadn't seen evidence of its use.

She also asked if the new Title IX counselor and "focal point" administrators reflected additional duties for existing employees or were new and separate positions.

"Same with 'teacher on special assignment - consent education,'" she said in a recent email. "What does this training consist of? Is it mandatory? Ensure that all students receive it? What training do TEACHERS and staff people receive?!"

Jacobs said the district response did not seem to address anonymous complaints, the leftover insurance money or the request for broader teacher education.

Her faith now lies with the Berkeley school community holding the district accountable.

"The public has been doing the work," Jacobs said. "This isn't the first time."

The plaintiffs hope the settlement and resulting publicity will serve as a springboard for crucial changes that still need to happen in Berkeley schools.

"We've held them accountable financially," Jacobs said. Now comes "holding them to their promises and ideals to improve the safety of the students."

Phillips said she is also skeptical. And she asks a looming question: Why has this taken so long?

"I'm grateful there have been improvements to Title IX, but these are basic things that should have been done with the induction of Title IX — and not a grand gesture of good faith," she said.

"This case has brought to light many cracks in what seems to be a systemic problem within BUSD and public education in general. Bissell was protected throughout and after his reign of terror at BHS, why?" Phillips asked.

One of the most frustrating and painful aspects of the Bissell ordeal for Phillips, she said, was how he stayed on the job for years after she and other students complained to school staff about his behavior.

She said she was abused by him during her four years of high school, from 1999 to 2003, and also when she coached volleyball after graduation. He taught at Berkeley High until 2021, though was put on leave during misconduct investigations.

Even when the district "released" him, Bissell's records were confidential, leaving his teaching credential intact. That allowed him to get teaching jobs in Oakland and Marin County, according to Phillips.

The state revoked his credential in 2022 — but Bissell can still teach at charter and private schools, she added.

"The lawsuit was always about protecting current and future students first and foremost. We have achieved a number of goals thus far, including the revocation of Bissell's CA teaching license and vast improvements to Title IX offices specifically at Berkeley High," Phillips said.

"I do feel proud to be a catalyst of change," she added. "It's in my blood."

Yearbook teacher helped put spotlight on past problems

Some aspects of the Bissell case are extraordinary.

In 2020, Phillips was contacted out of the blue by a Berkeley High yearbook teacher who was troubled by the now infamous 2003 yearbook picture of Bissell wrapping his arms around Phillips, nuzzling her neck.

The caption? "Most likely to date a teacher." A student had asked the yearbook teacher about the photo, finding it disturbing.

The teacher, Genevieve Mage, reached Phillips by phone in Oregon, telling her Bissell's behavior had been against the law.

Phillips told Mage she had complained to school officials at the time, more than once.

For four years, starting when she was 14, Bissell grabbed her in dark hallways and empty rooms, grunted, squeezed and nuzzled her, and made sexually suggestive comments, Phillips said.

She hated it.

Mage, who left the district at the end of the last school year (2023-24) learned that several other female students had experiences with Bissell similar to Phillips, with some telling school officials. Yet Bissell was still teaching.

Her call to Phillips effectively broke open the secrecy.

Phillips hired a lawyer and filed a new formal complaint against the district in 2020. In the same period, parent advocates organized to push the district to do something about Bissell and help students they said he had affected.

Mage, who said she left Berkeley High in large part due to the district's handling of the Bissell matter, said: "I have to have hope that BUSD will actually comply with the victims' nonbinding demands — because I certainly don't have faith."

Phillips called Mage a hero, and Mage said the same about Phillips.

Phillips couldn't push to charge Bissell criminally because the statute of limitations had passed. In 2023, Gov. Gavin Newsom eliminated those time limits in child sexual assault cases, but this wasn't retroactive.

Though in the settlement the district admitted no liability in relation to Bissell, its own investigation into Phillips' claims about him surfaced "credible" reports of inappropriate behavior involving several female students.

These details were only made public after local news site Berkeleyside, which broke the story and dug into it deeply, threatened to sue the district for access to Bissell's disciplinary records.

A different feel emerging

Rebecca Levenson, a deeply involved BUSD parent activist, said she sees positive stirrings finally happening after many exhausting years pushing the district on sexual conduct issues.

"Things have gotten better in the last three years, but especially within this last year," said Levenson, an expert in domestic violence prevention.

Among her many volunteer hats, Levenson is co-chair of the district's Gender Equity Sexual Harassment Advisory Committee, a member of the district's budget and safety committee, and the parent representative to BHS Stop Harassing, the student group that organized the "rape culture" walkout in 2020.

She said students "love and respect" Viteskic, the Title IX coordinator, who's held the job for three years.

"There is no question in my mind that that single hiring decision was essential to address some of the longstanding awful district response to survivors and their families," Levenson said.

She also said the new "special assignment" consent educator and the Title IX investigator are familiar district employees who are liked by students.

"When people feel comfortable and feel like they can trust you they're going to tell you so much more. What I would like to see happen is to enshrine these positions into our school district, so it's not at the whim of whoever is the superintendent at the moment," Levenson said.

She's still fighting for a bolstered consent curriculum at the elementary and middle school levels, she said.

Levenson is among several parents going back several years who've hammered the district to improve its handling of sexual misconduct. Going to meetings. Getting on committees. Sending letters.

She points to a 2014 case of a Berkeley High counselor accused by students of sexual misconduct, and student Instagram accounts sexualizing students behind their backs.

She talks of high turnover in Title IX coordinators, including stretches when the legally required position was vacant, not to mention spotty investigations and lax recordkeeping. Points also brought up in the Bissell lawsuit.

The work may be paying off.

Fresh optimism has also been expressed by at least some current Berkeley High students.

Two seniors in the BHS Stop Harassing group and two in the BHS Women's Student Union shared their thoughts with The Scanner. They all asked not to be named.

"Because of what happened with the Bissell case… there is some mistrust, it has trickled down," one of the girls said. "But I think there are important things that are getting better. For one thing, we have a Title IX coordinator and she's on campus."

Sexual harassment and consent education in classrooms and assemblies has also increased, they said. Same with posters in classrooms and hallways featuring information on legal rights and reporting.

"I've noticed a significant increase in education from my freshman year to this year," one of the seniors said.

What they'd like to see, most agreed, is more compelling education that's aimed more effectively at high schoolers.

"We need the presenters to actually know what they're talking about. We need it to be applicable to high school students. It needs to be interactive so that students actually learn how to apply it in real life," one said.

Another agreed: "There's enough consent education happening, it's just not in the right manner; it does need to be geared to high schoolers. Trying to present it in an adult fashion doesn't work. Presenting it too childlike doesn't work. It has to be a balance," she said. "I think that's a work in progress."

When it comes to Title IX, Berkeley Unified isn't alone

People watching the Bissell case have various theories about why it took the district so long to address his behavior.

They range from lax funding of the district's Title IX program, to the power of the teachers union in protecting its own, to a culture that accepts sexualized behavior from a teacher as creepy, but not necessarily wrong or against the law.

Berkeley isn't alone in Title IX challenges, said Maha Ibrahim, a managing attorney at Equal Rights Advocates, a legal advocacy nonprofit in San Francisco. It's more the rule than the exception, she said.

Ibrahim closely followed the Bissell case.

"One of the issues with all the school districts that we've encountered is that even if they have good policies on the books, they never change their approach to underfunding the issue of sexual assault and harassment," she said.

Title IX has some compliance wiggle room, intended to accommodate smaller and larger school settings, she added.

"The other issue that's happening with Title IX is you have a bunch of adults dealing with a lot of things they don't want to deal with, sexuality and sex with a bunch of kids. If you're not trained, your instinct is to make it go away because it really is uncomfortable to address. This is easy with students because they are by nature transient."

Like others, Ibrahim has seen improvements in Berkeley Unified in recent years.

"I think it's headed in the right direction," she said.

After Berkeley High sexual misconduct case, wounds remain

Bissell's case was handled by the school's Title IX office, as legally required.

But the process was incomplete, stalled and haphazard, according to the lawsuit filed by the former students in 2021.

"For Title IX to work, you have to follow the rules, and have an administration that will follow the rules," Levenson said.

Of the district's actions since the lawsuit, Levenson said: "It's been a 10-year fight to get these kinds of changes fully realized."

"I knew the only way, given the resistance of the system and the [school] board, for anything to change was to keep pushing and keep pushing and keep pushing in the name of every single one of those survivors," she said.

"Do I think our system owes our students not only an apology but action?" she asked. "Hell yes."