Ben Brown: Chef, loving uncle, 'champion of the people'

"He stood up for his rights, he stood up for everyone else's rights," said his niece, Angie Perkins. "He just honored everyone."

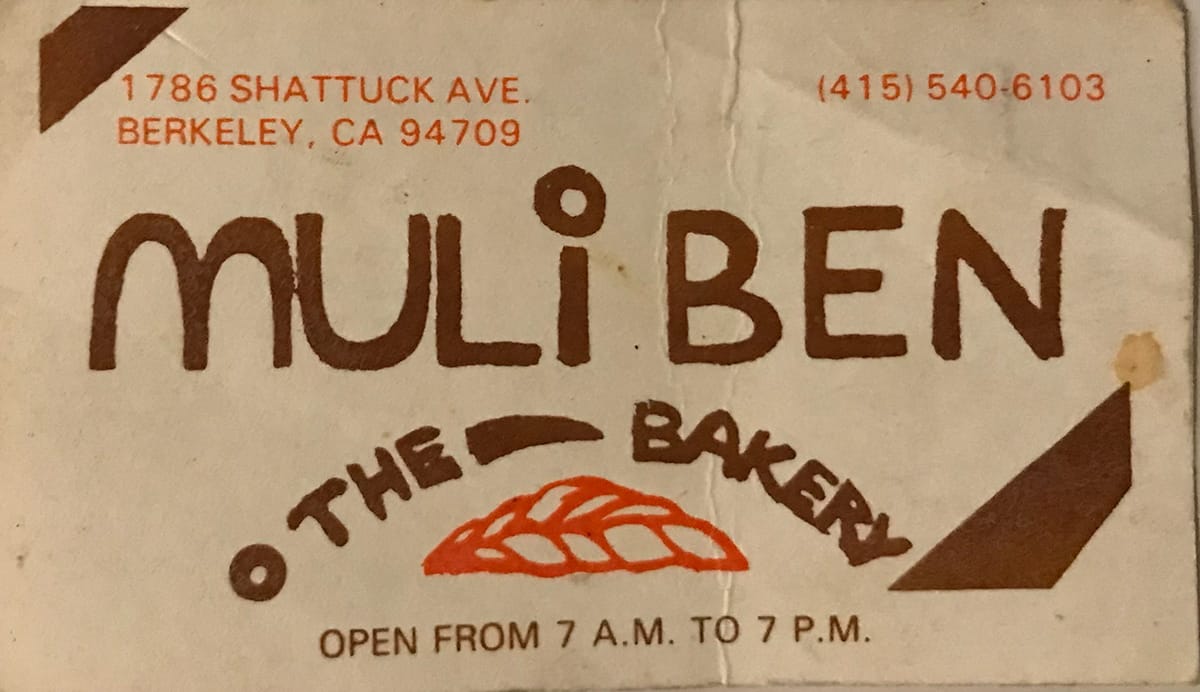

Berkeley is mourning the loss this week of 78-year-old Benten "Ben" Brown, an activist and art lover who was a familiar face for years at Berkeley Hort.

Brown died last week when a driver struck him at Rose and Josephine streets as he walked home from Martin Luther King Jr. Middle School.

He was there to see his best friend's son play his first King soccer match.

"He gave all the kids a hug. He asked me to send him the schedule for the next game. That was it," said Matthew Faircloth, Brown's best friend of 25 years.

"He was very loving, very kind, but also very stern in his beliefs, in a good way," said Angie Perkins, Brown's niece. "He stood up for his rights, he stood up for everyone else's rights, very actively. He just honored everyone."

Brown was the kind of person who would never miss a milestone, not only graduations and weddings, but also children's birthdays and sports games.

He never hesitated. He was always there.

"He wanted to spread love. He always tried to show everyone that they were valuable," Perkins said.

"He just never walked past a person," Faircloth said. "If someone came into his space, he always said hello or good morning or how are you."

Ebony Davis, Brown's great-niece, flew to California to visit him earlier this year. She got to know his morning routine.

After warming up his coffee, he would set out on a long walk through the neighborhood.

She was amazed by everyone he introduced her to along the way.

"You gotta meet this couple, they're normally out at this time," he would tell her.

Not only did he know countless neighbors and friends, he also knew their dogs by name.

"Everywhere we went, he knew people and they knew him," she said. "He was so well-known and so loved."

Brown was also the kind of man who would go to Kaiser to pick up his prescriptions rather than having them sent to his home.

"He wanted to go in and see the people, say hello," Faircloth said. "I think he had these relationships. He was close to so many people."

That included his regular bus driver. Friends said Brown got around on foot or public transit. Only one person described ever seeing him behind the wheel. It was decades ago and only once.

Last week, Brown was pronounced dead at Highland Hospital a few hours after the crash in North Berkeley.

The hospital called his niece, Angie, to give her the news. She alerted Matthew Faircloth.

"My whole world turned upside down from that point on," he said.

Faircloth then began the difficult work of letting Ben's many friends know what happened.

Over the weekend, Faircloth and others put up a memorial at the crash site.

Close friend Stephanie Mackley worked with Faircloth to create a GoFundMe page to help Brown's family with arrangements related to his death.

As of Monday, it had already raised more than $9,000 of its $25,000 goal.

"He was a Berkeley legend," said longtime friend Nikki Kyner. "You couldn't walk around in Berkeley, particularly North Berkeley, without him being greeted warmly by people. At a farmers market, you couldn't get anywhere."

Kyner recalled how Brown had come to Alta Bates Hospital when her daughter was born 23 years ago.

To mark the occasion, he brought her a cornish game hen in an apricot glaze, a small glass of red wine and a rose in perfect bloom.

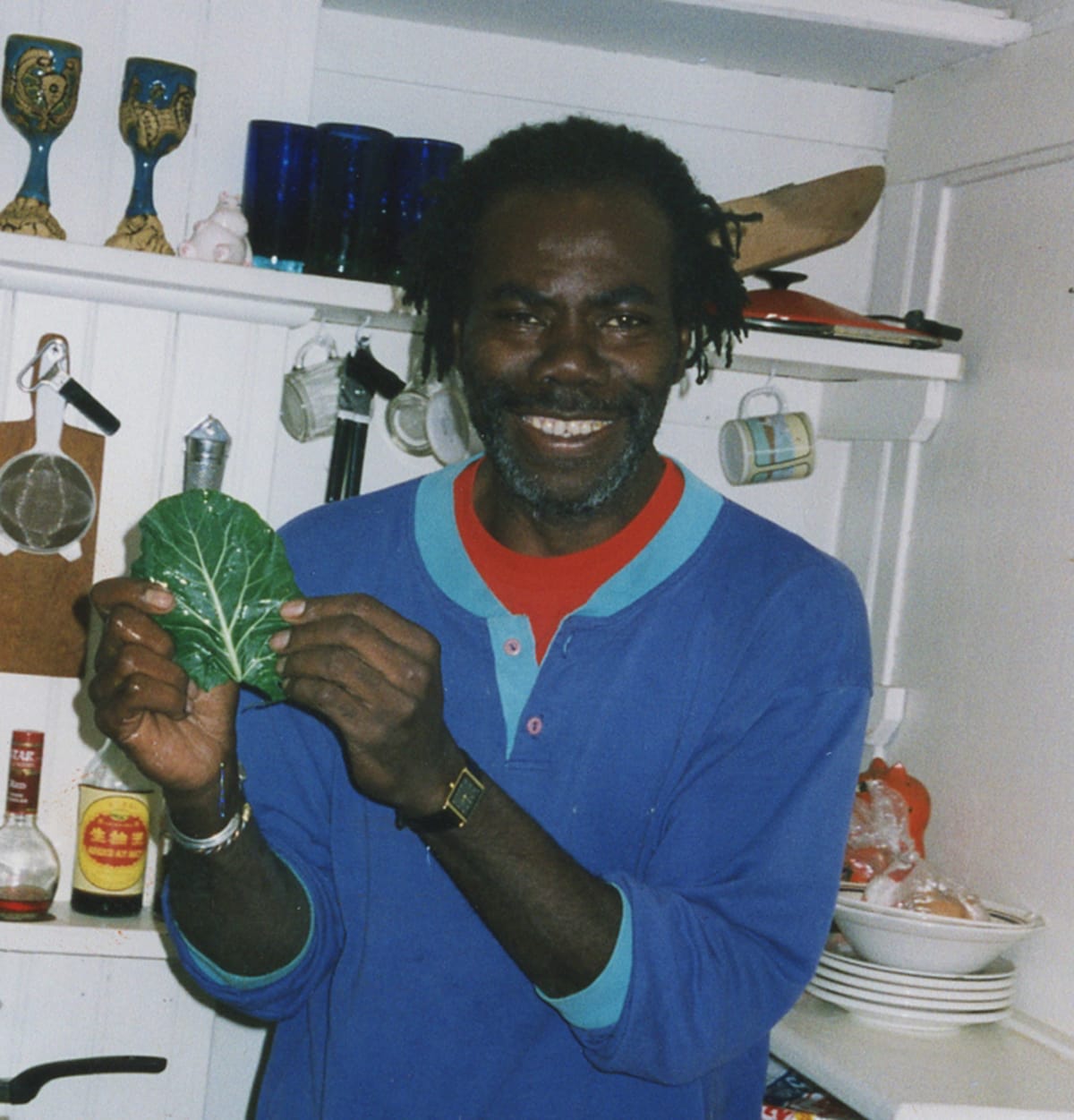

"He was a helluva good cook," she said. "He made the best gravy on Thanksgiving."

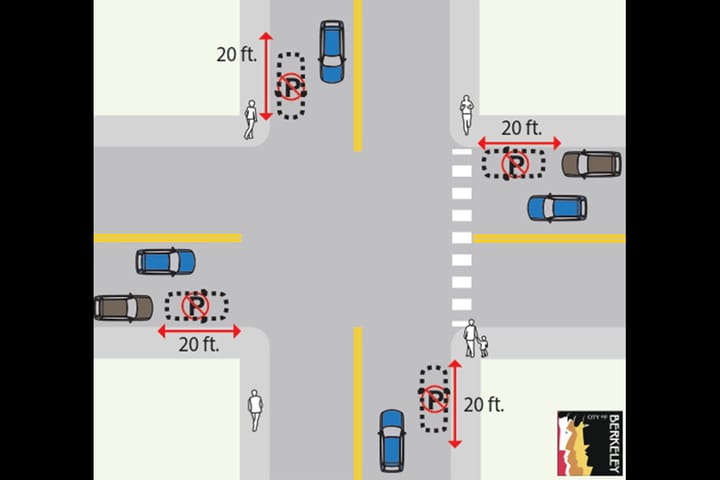

Kyner met Brown in 1984 when she stopped on Shattuck Avenue to go to the dry cleaner.

She got sidetracked by a delicious smell coming from MuliBen Bakery down the block at Shattuck and Delaware.

"I popped out of my little convertible (a '63 Spitfire) and I had to go in," Kyner said.

She left the bakery with a job she'd had no intention of getting.

But the connection had been immediate, and she could tell Ben and his partner, Muli, needed someone in the front of the house while they made magic in the kitchen.

"We were friends. It got to that so quickly," she said. "It's like falling in love at first sight."

Ben had a deep voice, "like Darth Vader," and he laughed all the time, Kyner said.

"He lived a huge life," she said. "The fact that he's gone is hard for a lot of people."

The bakery was a neighborhood institution, full of art and music. The food was a combination of Jewish and Southern cooking.

"Ben would make sweet potato pies. Muli would do knishes," Kyner said. "The food was insane. It was amazing."

The MuliBen era. From left: Muli and Ben at the bakery; Ben and a wild Berkeley peacock with an unidentified friend; and the MuliBen business card. Nikki Kyner

Kyner recalled how, at the time, Berkeley had wild peacocks that would turn up in the alley behind the bakery to eat day-old muffins.

Every Thanksgiving, Muli and Ben would open the bakery to the community and host a dinner for anyone who had nowhere else to go.

They cooked turkeys, sides and soups. There was wine and great music. It was a fabulous event.

"They weren't getting rich at the bakery. It was always a struggle," Kyner said. "But they were celebrating the fact that they could share. They just did it because they wanted to and they could. And they knew it was important."

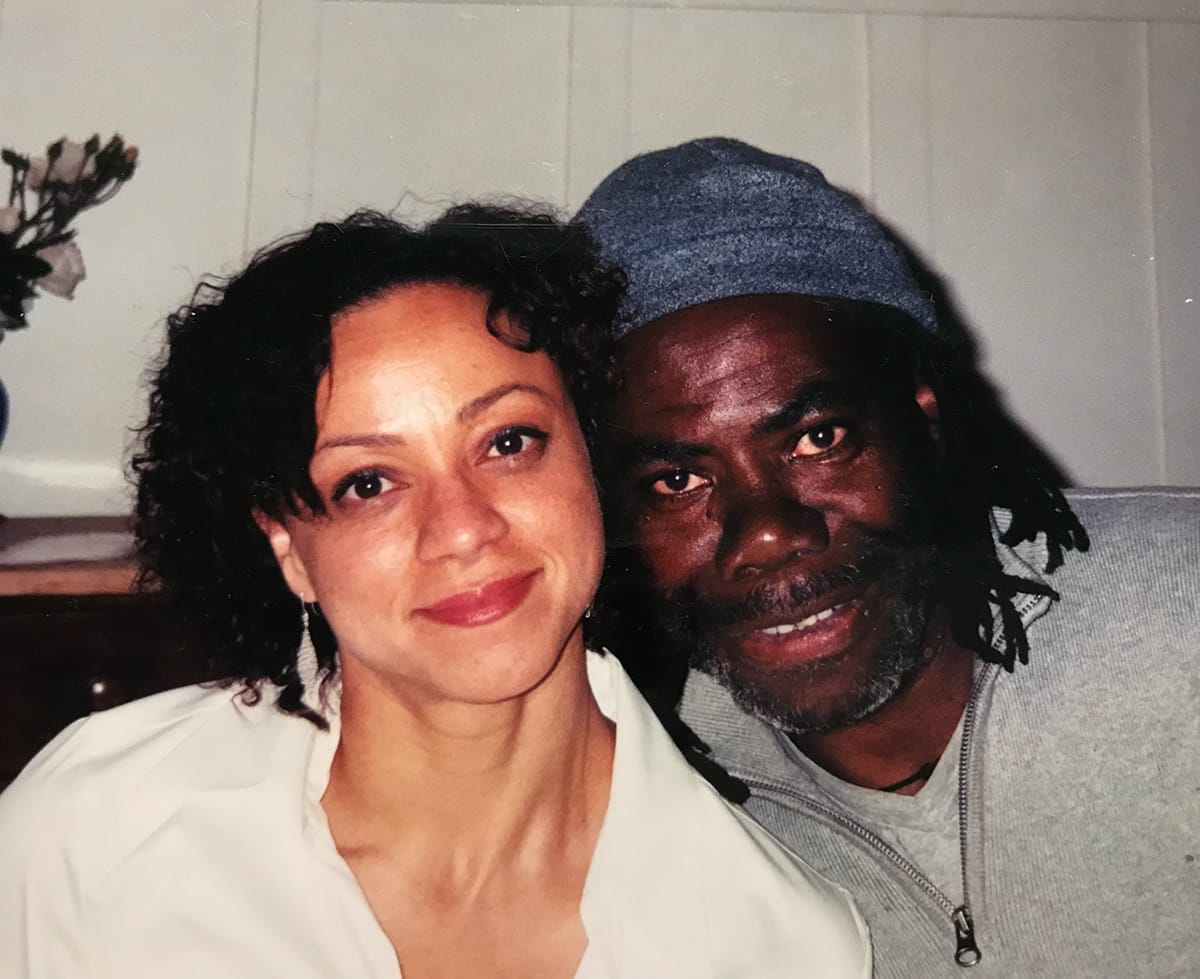

Muli and Ben had come to Berkeley together from New York City.

Muli was the love of Ben's life, Kyner said. He died in the early '90s and the bakery closed.

Left: Ben and Matthew at the Red Cafe on University Avenue. Right: Outside the Red Cafe. Courtesy

Brown later went to work at the Red Cafe on University Avenue. That's where he met Matthew Faircloth. They struck up a friendship that would be with him for the rest of his life.

Matthew's father, Ian Faircloth, had a print shop called Canterbury Press at University and Bonita avenues. But he always wanted to open a cafe.

When the space next door became available, Ian took it over and opened the Red Cafe. He hired Ben as the chef. Matthew was just 17.

Matthew said he remembered Ben Brown walking into the cafe wearing small white shorts over his long beautiful legs. He was carrying a backpack and a tennis racket.

"I was like, who's this cool guy?" Faircloth said. "He would just tell stories. We would sit around and listen to Otis Redding, R&B. We kinda became great friends — even though he was almost 30 years older than me."

Faircloth remembered the connection as instant. Ben quickly became part of his small crew of young friends, riding around in Faircloth's Toyota Tercel.

"We stood out in a crowd," Faircloth said. "It's like a giraffe and an ant hanging out. On the outside, we looked very different but, on the inside, we were very, very close."

They had a shared passion for music, listening to dancehall reggae, Sarah Vaughan, old-school R&B and Nina Simone, who Brown had seen repeatedly in New York City.

They went to music clubs all over the Bay Area and saw shows from Sade to Steve Earle, including when he used his music to protest George Bush.

Faircloth recalled driving in the car with Ben, Ben's arms swinging as he danced in the passenger seat, full of exuberance and excitement.

"If it was a jam, Ben's in it," Faircloth said. "If the music's going, Ben's arms are swinging. He's gone. He's in the moment."

Left: "Uncle Ben" with Ben Brown and Jackson Barnett and Juliette Kyner. Nikki Kyner | Right: Ben with Ella Faircloth and her brothers. Matthew Faircloth

As Faircloth got older and became a father, Ben became "Uncle Ben."

He took the role seriously, attending every Berkeley High volleyball game for Faircloth's daughter, Ella.

"My kids kinda became his kids," he said. "The people he was close with, he adopted those kids as his own."

That was true for Nikki Kyner, too, and her children Jackson Barnett and Juliette Kyner.

After Ella's volleyball games, Brown would stay on to watch the other BHS teams, getting to know all the players.

Brown's true passion was tennis. He came from a family of tennis lovers — they didn't all play but they loved to watch.

Ben would fly to New York and travel internationally to see big matches. In Berkeley, he would play at the Berkeley Rose Garden.

"When he couldn't play it, he watched it," Faircloth said. "The only time I didn't hear from Ben was when Wimbledon was on."

Aside from that, they talked every day for 25 years, wishing each other goodnight, checking in at 6 a.m.

Faircloth said Ben was a person who could hang out with anyone. That included going to the senior center to keep much older men company.

"I still can't believe he's not here," Faircloth said.

Brown was originally from Georgia, where his family plans to hold a celebration of his life Saturday.

He was one of 12 children to parents John W. and Cotis Brown. Most of his siblings — Rebecca Talton, Kay Dixon, Frankie Johnson, Betty Jo Hart, Heddy Roberts, Sidney, Douglas and Tony Brown — preceded him in death.

But two sisters, Mable Swain and Joyce Perkins, and brother Sammy Brown survived him, along with many nieces and nephews.

Cotis was a homemaker and John W. Brown worked for Armstrong Industries, a manufacturing company.

When Ben was growing up, they made Frankie, who was eight years older, take him with her as a "chaperone" when she began seeing movies with friends.

"Moreso like a spy," Perkins said, laughing.

Of all the siblings, Ben was closest to Frankie. They talked daily until her death eight years ago.

From left: Ben with two of his sisters, Betty and Joyce. Ben and niece Angie Perkins. Ben with his trademark smile. Courtesy

His niece Angie Perkins, daughter of Frankie, said Ben first left Macon, Georgia, for New York City, where he spent at least 20 years.

In New York, Ben was a big part of the disco scene and loved dancing at Studio 54.

"He really partied," Perkins said. His friends said Ben was a beautiful dancer with natural rhythm.

From New York, he and Muli moved to Berkeley. Ben was attracted to the values and atmosphere of the liberal community.

"He was a free-spirited person," Perkins said. "His lifestyle was more acceptable and supported there."

In 1987, when Perkins was in her early 20s, she went to California for a several-week visit.

"I was kind of wild and having a hard time with myself," she said. Ben encouraged her to come out for a change of scene. She ended up staying five years.

Perkins worked at MuliBen and spent a lot of time with her uncle. It was an important time in her life.

The cafe had a special atmosphere. The people who came were regulars, drawn not only to the art, music and delicious pastries — but also to Ben.

Berkeley native Helen Hallberg often went into MuliBen for zucchini bread.

"It was kind of a ritual," she said. Her brother lived in an apartment nearby and Ben would always ask about him.

She later worked with Ben at the Red Cafe, which she helped run after managing Au Coquelet on University Avenue for many years.

Ben was "the talent" and Hallberg ran the operation. Both were avid walkers and would run into each other around Berkeley years later, including at kids' sports games.

Even decades later, Ben always asked Hallberg how her brother was doing. He had that way about him.

After the Red Cafe, Brown got a job at Berkeley Horticultural Nursery, at McGee near Hopkins Street.

Paul Doty, Berkeley Hort president, said he first met Brown 30 years ago at King middle school, just a block from the fatal crash site.

They were both attending a meeting organized by Alice Waters, who was working to get the Edible Schoolyard Project off the ground. It was 1994.

"I came away from that meeting really energized," Doty said.

He ended up walking home that night with Ben Brown. They became fast friends. A few weeks later, Doty hired Brown to work at the nursery.

But the relationship was bigger than that. They spent a lot of time together, drinking coffee at the original Peet's and at FatApple's on MLK.

They would see jazz musicians at Yoshi's, including Esperanza Spalding and Kenny Burrell. They would hang out at the Cheese Board Collective, where Brown also worked for a time.

They spent a lot of time walking around Berkeley together.

"He was a real walker," Doty said. "He was a part of Berkeley Hort for a long time. This is all very sad."

At the nursery, Brown mainly focused on plant maintenance, watering and transplanting. But he was also good with people.

"Ben was one of those people," Doty said. "There was just a vibe, at least for me. He was just sincere and calm and easily relatable."

As Brown got older, his niece, Angie Perkins, sometimes urged him to move back home.

"You need to come to Georgia where you have some people," she would tell him. "He would think about it, but he didn't want to leave his friends."

"I know we're the blood relatives," she added. "But Matt, a lot of people there, really loved him. He really loved them as well."

Perkins recalled one time Ben came to Georgia for the holidays. He always came bearing gifts, trinkets for the kids and other presents.

This time, it was right before Christmas. Ben showed up with a 20-pound fish in a bag of ice.

"You had the fish on the plane?" she asked him, incredulous, in part due to the smell.

"Oh yeah, I had it on the plane!" he said.

Brown was a very good cook — and could be critical when it wasn't done right. He loved good wine, too.

He came from a family of cooks. Ben had no traditional training but approached the kitchen like a chef. He loved to make lamb, among other things, and enjoyed different spice and herb combinations.

"He just kinda knew what went with what and what you should do," Perkins said. "He couldn't stand it when someone overcooked something."

Close friend Nikki Kyner said she wasn't surprised to hear Ben had taken a plane to Georgia with a massive fish in tow.

In Berkeley, he loved shopping at Monterey Market and also Monterey Fish Market, just up the street.

"I remember going in there and they were just giving him fish, saying, take this, this is really good today," Kyner said.

At the time of his death, Brown lived at Harper Crossing in South Berkeley in an apartment filled with plants and art he had collected throughout his life — everything from pieces he'd bought from street artists to fine art, from sculpture and paintings to creations made by his friends' children.

He loved going to museums, like the de Young, and seeing the latest exhibits.

Ben loved people and it was clear they loved him too. It showed in all of his relationships. His encouragement knew no bounds.

"You can dunk that basketball," Kyner recalled Ben telling her.

"I'm 5'4!" she said.

"You can do it!" he'd say.

"He believed in people in a way that allowed them to see their potential and not worry about their circumstances," Perkins, his niece, said.

That was especially true with children.

"He just believed in them wholeheartedly, the person that they were going to become," Perkins said. "They were special and gonna be special, gonna grow up that way, live as adults that way."

Brown could get upset, just like anyone. He could be a "grumpy old guy," too. He was angry about a lot of things in the world, loved ones said.

But he also loved people and had a deep compassion for them.

Ben Brown was was a lifelong activist. Photo at UC Berkeley by Ebony Davis. Obama poster photographer unknown.

When his great-niece, Ebony, visited him in Berkeley, one of the places he took her was UC Berkeley for a protest over the war in the Middle East.

He was a lifelong activist, attending the Million Man March in DC in 1995, among many other marches.

He loved Cornell West and James Baldwin and was passionate about Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X.

He was deeply concerned about systemic inequities faced by minorities. He was a staunch critic of war.

"He was always at every protest," Faircloth said. "He was politically involved and caring about any sort of issue that affected people. If people were suffering, he was a champion for that cause."

"He was very much a champion of the people," Faircloth said.

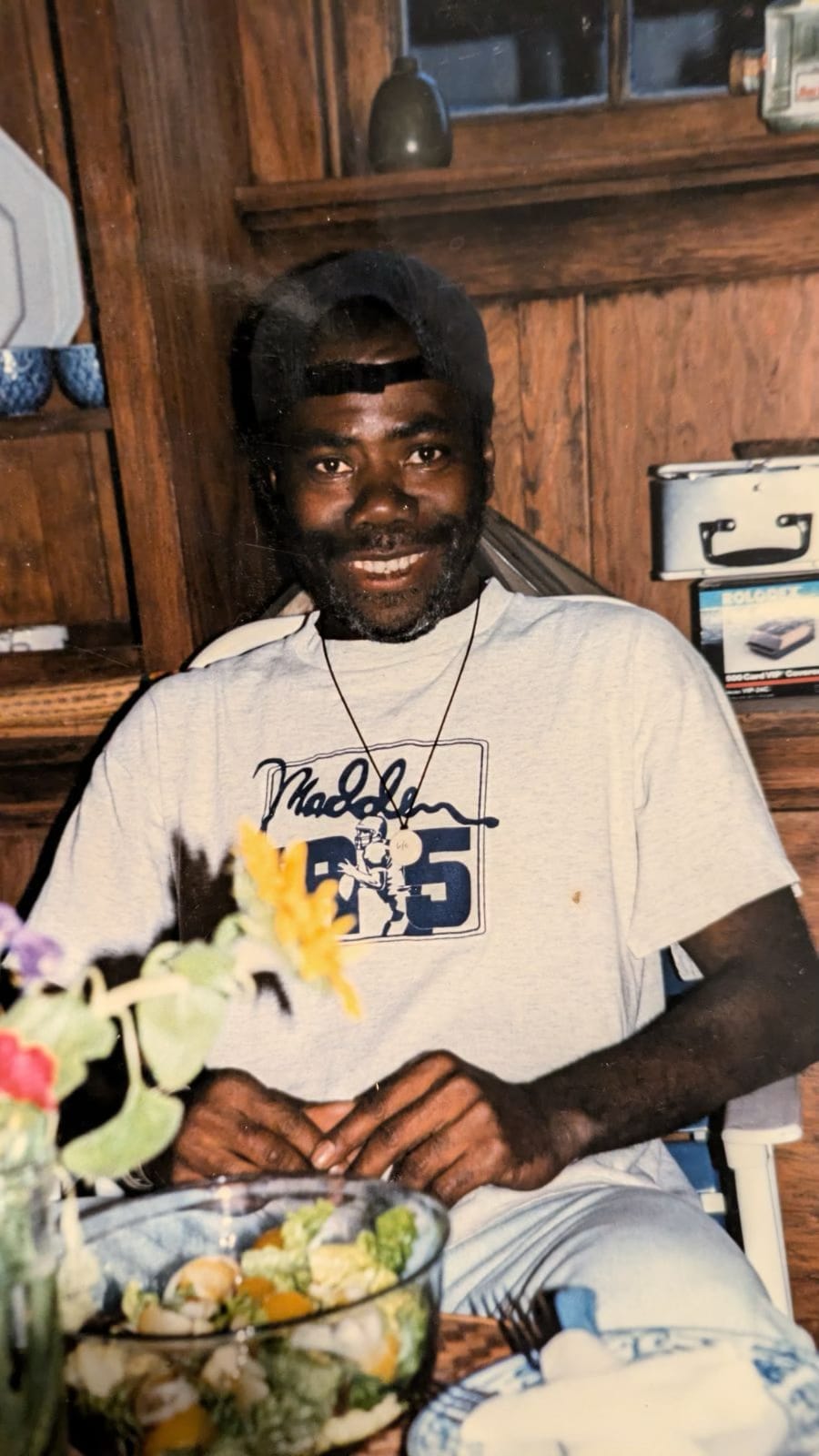

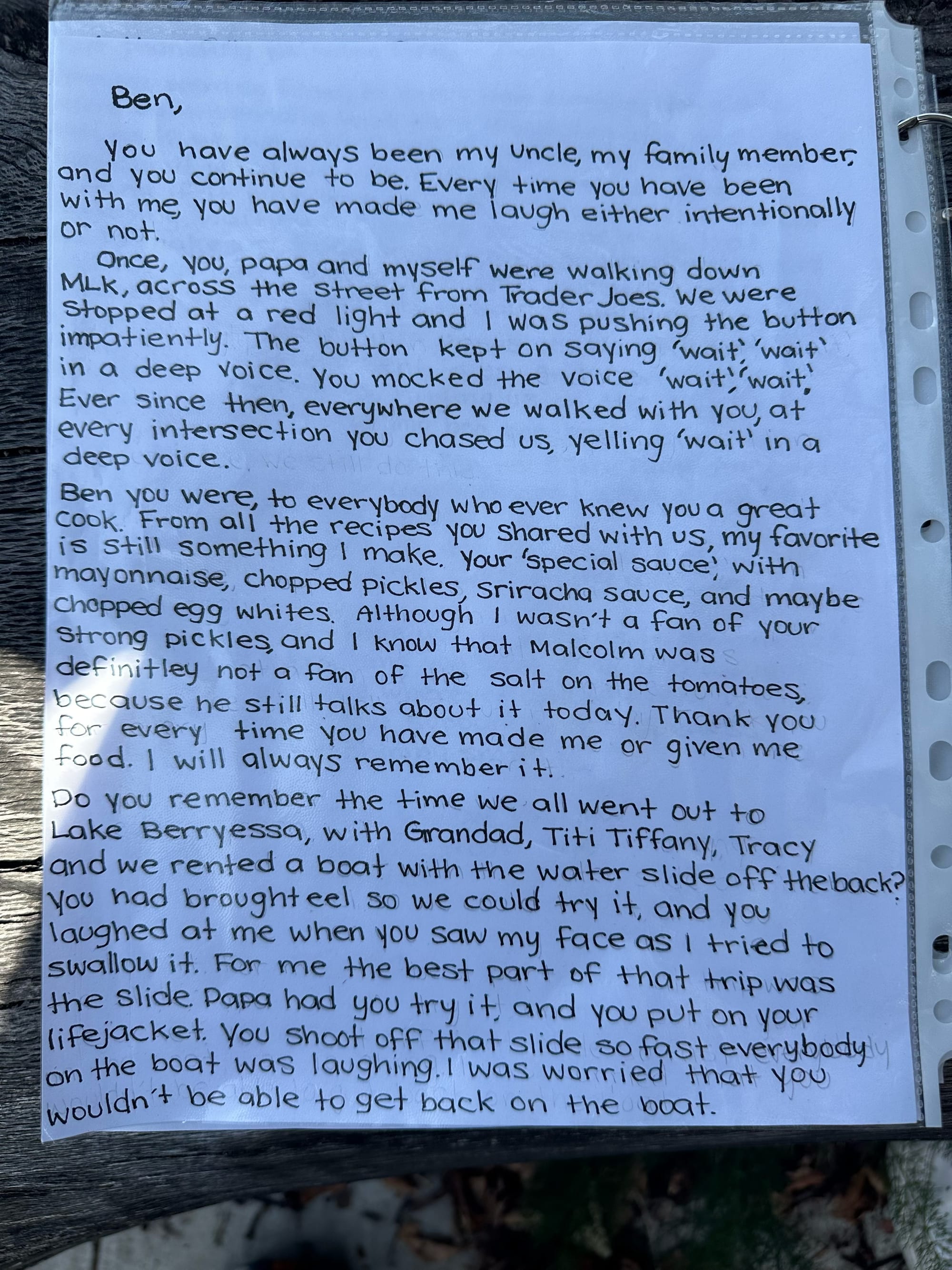

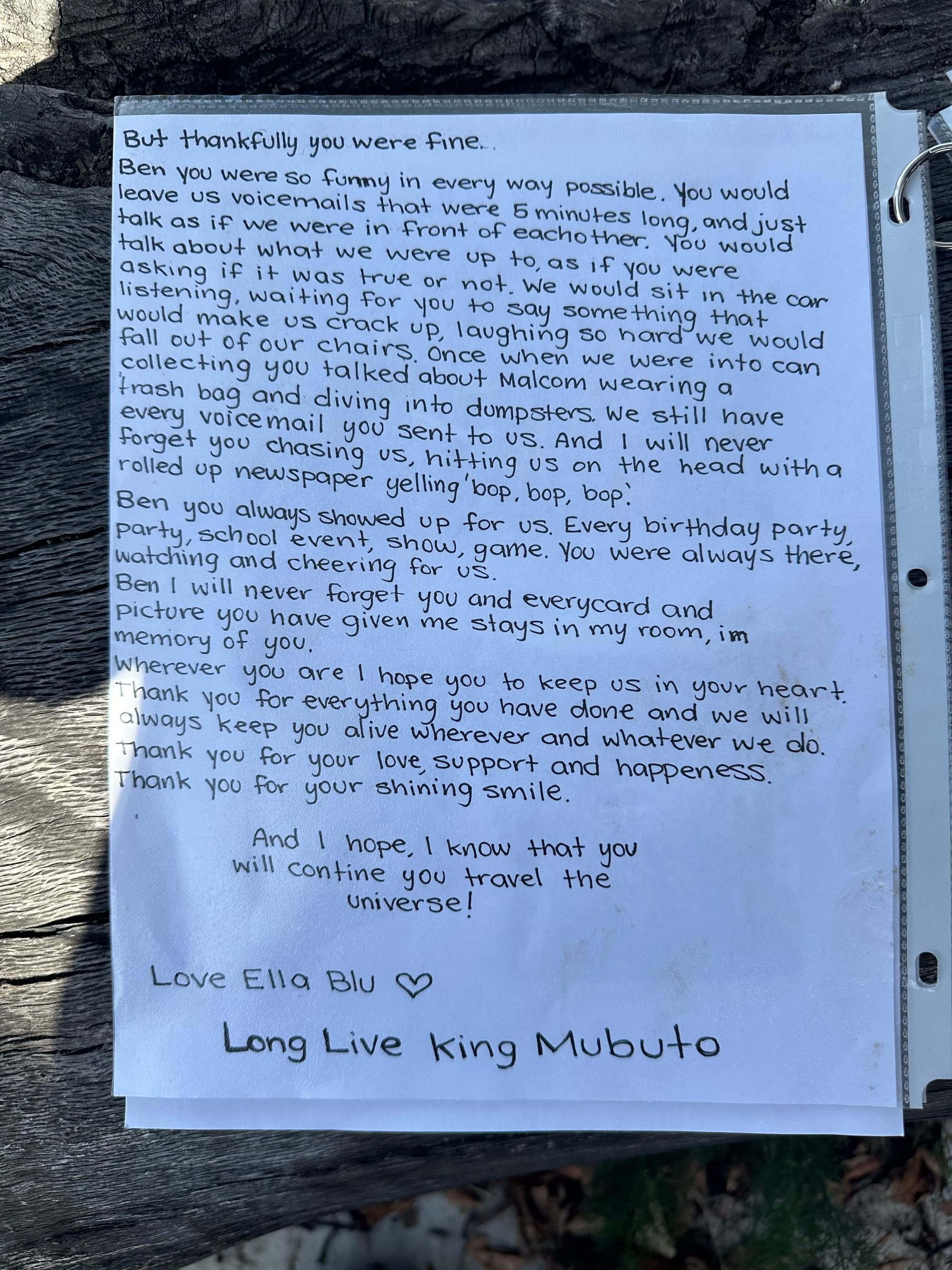

Ella Faircloth and her letter. Matthew Faircloth | The memorial for Ben Brown at Rose and Josephine streets. Helen Hallberg

Over the weekend, Faircloth and others went up to the intersection where Ben Brown was killed to install a memorial to honor him.

In an odd coincidence, Brown once rented a room in a house right on the corner.

Faircloth said he's planning a large party, likely in January, to celebrate Brown's life.

"Ben was a person of the people and he liked to have a good time," he said. "He would be the one you had to kick out at the end of the night: 'You're 90! Let's go to bed!'"

Over the weekend, people placed flowers and hung photographs all around the intersection.

Some, including Faircloth's daughter, Ella, left heartfelt letters.

"You were so funny in every way," she wrote. "You would leave us voicemails that were 5 minutes long, and just talk as if we were in front of each other.… We would sit in the car listening, waiting for you to say something that would make us crack up, laughing so hard we would fall out of our chairs."

"You always showed up for us," she wrote. "I will never forget you."

Learn more about Ben Brown and make a contribution on his GoFundMe page.