Berkeley police staffing still a struggle, consultant says

The analysis found that officers are often spread thin with little time for proactive policing, particularly as calls for service have rebounded.

The Berkeley Police Department needs to add 15 officers to its patrol teams and boost the ranks with community service officers to help with morale, burnout and overtime spending, a recent analysis found.

The recommendations were among 54 suggestions from consultant Citygate Associates, which took a close look at BPD's staffing and workload as part of Berkeley's years-long effort to reimagine policing in the wake of George Floyd's death in 2020.

To be clear, Citygate did not recommend changing Berkeley's overall number of authorized officers. But it said the current approach of filling open beats through overtime spending needs to change.

"It's a mistake, truly a mistake, to just stick to the overtime route because it's burnout, it's fatigue," a Citygate rep told officials. "An officer who's fatigued is more likely to take shortcuts and more likely to get him or herself and the city in trouble."

Citygate presented its findings to the Berkeley City Council in a worksession last week.

The city budget allows BPD to hire up to 181 officers — but Berkeley has struggled for years to fill those positions, at least in part due to a nationwide shortage of interested candidates.

Despite 150-160 officers on the books, the number of BPD officers available for solo duty has often hovered in the 120s-130s due to injuries and leave.

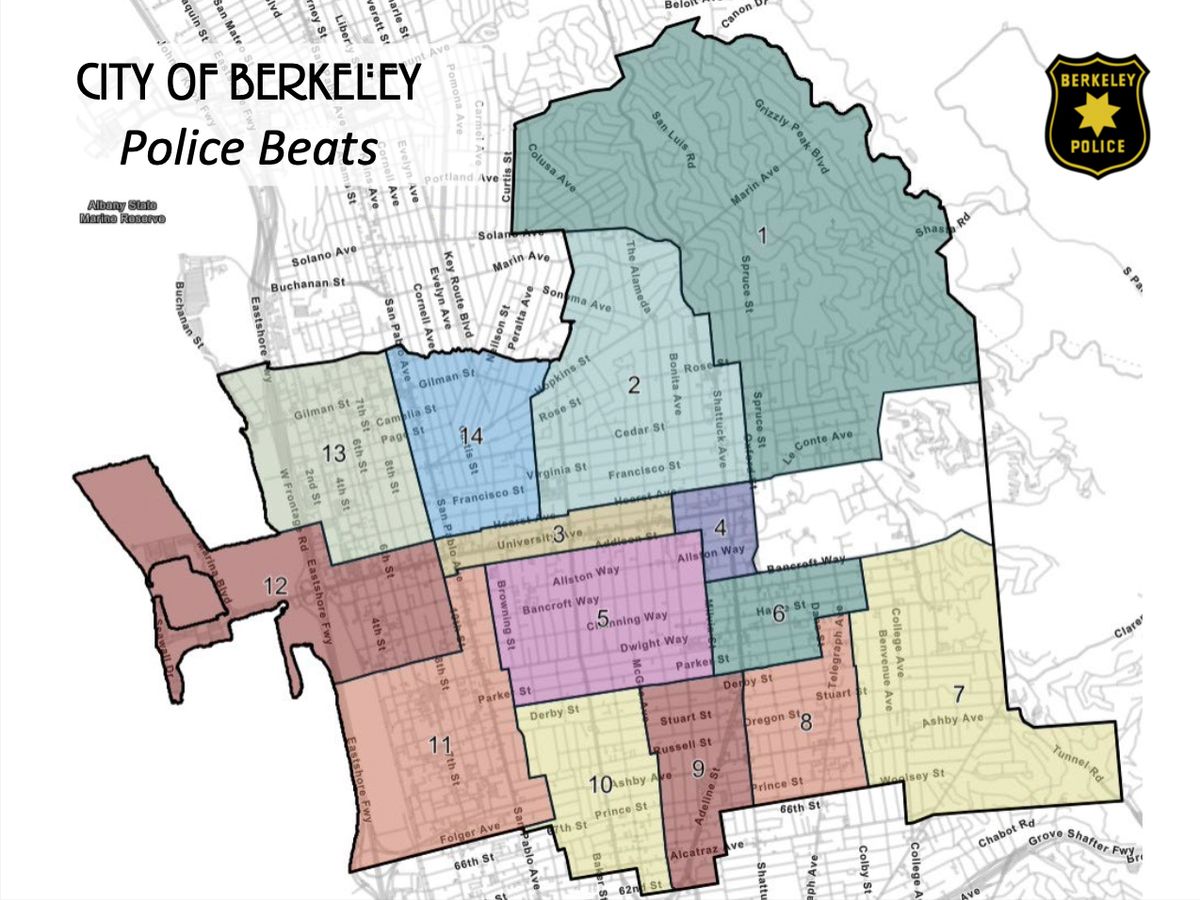

And the number of beat officers on patrol has now bottomed out at about 60.

As a result, the Citygate analysis found, Berkeley officers are often spread thin with little time for proactive policing, particularly as calls for service have rebounded from pandemic lows.

"We absolutely agree that rebuilding our patrol strength is critical," Berkeley Police Chief Jen Louis said Tuesday night. "And while our officers are delivering what I think is exceptional emergency response service despite the staffing constraints that they're under, they are absolutely impacted by the current deployment levels."

There are reasons for optimism, the chief said.

The city recently brought on a new recruiting firm that has increased the number of qualified applicants showing interest in Berkeley.

But sustained growth will take time, Louis added: "We can reasonably expect to add five officers annually over the next three to five years," she told officials.

Fortunately, sworn officers aren't the only solution.

BPD is already working to bring on new community service officers who will help pick up the slack on tasks that don't require an armed, immediate response.

On Tuesday night, Mayor Jesse Arreguín described how Berkeley had emphasized a "balanced approach to public safety … that integrates traditional policing with proactive community investments" such as the Specialized Care Unit and the city's new gun violence intervention program.

Officials said they want to keep investing in alternatives but also noted that the Specialized Care Unit (SCU) has a long way to go to fulfill its promise, particularly as it works toward 24/7 staffing.

The team is currently available 24 hours a day aside from regular closures Wednesday through Saturday from 4-8 p.m., the city said.

So far, the SCU has taken on about 1% of BPD's calls, a far cry from the 12% of BPD calls an early city audit found it might eventually divert.

Since the SCU launched about a year ago, staff said it had gotten about 1,500 calls for service and been dispatched to about 800 of them.

About 700 of those calls did not involve police.

The SCU is currently getting three to seven calls a day, staff said Tuesday.

But it's only averaged about two calls a day since launch, Councilman Mark Humbert observed.

"Clearly, the need is much greater than that and, given the level of investment, which is significant … I look forward to the response levels increasing dramatically," he said. "Overall, I'm struck by the fact that we put a lot of resources into the planning phases of this effort, but now, due to a variety of factors, are being compelled to delay implementation."

Council members said they hope to see the SCU take on more calls as time goes by, the result of increased staffing as well as better publicity.

Those calls could include nonviolent incidents that may now come to police or other crisis calls that have no need for police intervention.

Humbert also noted that BerkDOT, Berkeley's plan to remove armed police from traffic enforcement, may never come to pass due to existing state laws. He said he didn't see those restrictions changing.

"It may be tempting to jump the gun or spend beyond our means," he added, "but I don't want to end up in a situation where we're stuck with insufficient public safety staffing while also failing to fully stand up other programs or departments."

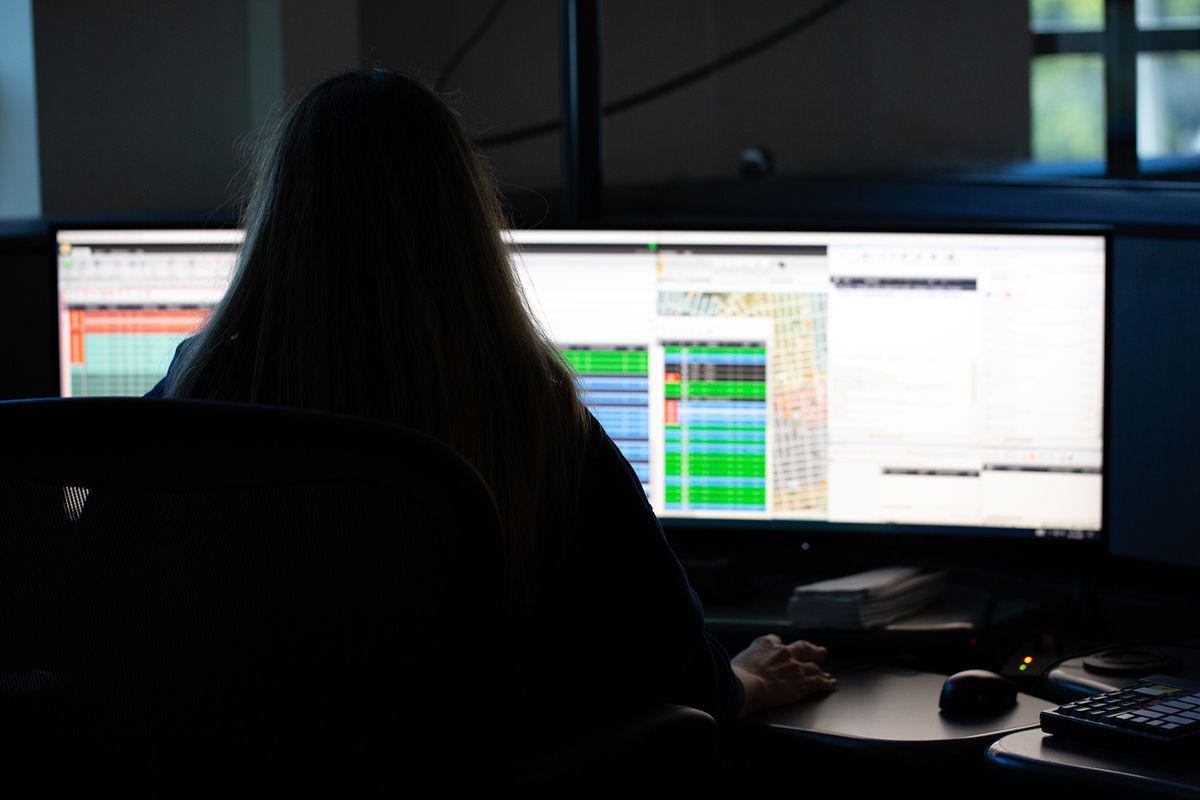

In addition to adding officers on patrol and community service officers across divisions, Citygate said Berkeley should also add dispatchers, fully staff the traffic unit, accept more reports online, and consider adding a second school resource officer, among other recommendations.

Citygate said it would also be smart for Berkeley to overhaul its requirements for reporting on the lowest level of force to reduce the burden on supervisors and give them more time in the field.

Level 1 uses of force, which involve contact but no report of pain or discomfort, make up the majority of BPD use-of-force reports.

Under the city's current rules, a police supervisor must review body-camera footage and interview witnesses for Level 1 uses, which Citygate said is out of step with other agencies — which don't categorize this type of contact as force at all.

Citygate said Berkeley should continue to document those reports but drop the need for a supervisor's review except when body-camera footage is not available.

Throughout the night, officials also acknowledged BPD's progressive vision, noting that the department "uses very low levels of force" and has "very low levels of sustained complaints" compared to other police agencies.

Council members and the police chief alike spoke about their commitment to a balanced approach to public safety where old and new systems work together.

Mayor Arreguín said he wanted to push back against the "false narrative … that reimagining public safety and supporting our police are mutually exclusive."

He noted that it would likely be his last chance to share his vision for public safety in Berkeley as he steps down this month to seek higher office.

Arreguín said he wanted to be clear that Berkeley is committed to funding a "well-staffed, responsive police department" while also acknowledging that reaching full staffing will take time.

"We're fortunate to have a department that's committed to progressive community-focused policing. One that has worked tirelessly to avoid the tragic situations that we've seen in other cities," he said.

Arreguín also acknowledged that, going forward, the city would need to invest in a modern dispatch system and find longterm funding for violence prevention and the Specialized Care Unit.

"At the end of the day, it's about building the best model for Berkeley," he said.