Dispatch from Berkeley wildfire season: Cut, whack, yank, dig, repeat

Home inspections, a "fuel break" on Grizzly Peak and a project focused on eucalyptus understory cleanup are just a few of the efforts underway.

Seasoned East Bay weather watchers know not to be fooled by summer's end. Especially when it comes to wildfire. The worst fire conditions typically hit in early fall, with a spate of searing temperatures coupled with strong, dry "Diablo" winds.

Of course, "typical" is disappearing from the weather lexicon, replaced by increasing unpredictability, a shift many experts link to climate change.

All the more reason to prepare, emphasize wildfire specialists. This includes Colin Arnold, the interim assistant Berkeley Fire chief overseeing the Wildland Division.

And as wildfire mitigation's summer season winds down, when fire inspectors criss-cross the city's highest-risk neighborhoods poking around with iPads in hand, Arnold says he's feeling pretty good about this year's efforts at taming Berkeley's most fire-prone landscapes, the dry grasses, weeds, brambles and branches that make especially good tinder to flame.

Still, he acknowledges, preparing for wildfire is a long-haul work in progress.

"Lots are cleaned up, vegetation trimmed back and neighbors [are] working with neighbors to get the work done," Arnold said.

"I have seen more arborist companies in the hills working to limb up vegetation and maintain tree health than I have ever seen before, and all of this points, to me, to a community that is beginning to believe that their best chance of survival of their property is not luck, or insurance, or anything other than the work they do to create a resilient community."

It's the law: Buffer your home from wildfire

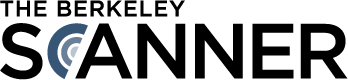

Arnold's talking about property owners in Berkeley's highest wildfire hazard areas, a stretch of around 9,200 parcels mostly in the hills near East Bay Regional Park District land.

Under state law, these property owners are required to mow, rake, thin, trim and remove vegetation from their houses or other buildings out 100 feet, called defensible space.

CalFire, the state's fire agency, sets minimum defensible space requirements.

But it's up to local fire departments to enforce them.

Protect your home from wildfires with defensible space! Divided into zones, it shields against fire spread, starting from your house outward. Each zone requires specific requirements for safety. Learn about Zones 0, 1, & 2 for effective protection: https://t.co/vKZa4oRwYe pic.twitter.com/xjOVb0XdRu

— CAL FIRE SCU (@calfireSCU) April 24, 2024

Data consistently show that defensible space helps prevent buildings from going up in flames, and gives fire crews space to work, to defend structures.

The strictest required clearing is near the base of structures, an area called "zone zero" or an ember-resistant zone, with incrementally more vegetation allowed further out. Defensible space addresses vegetation location, height, spacing and thickness.

CalFire also calculates wildfire severity hazard zones statewide, using factors such as weather, topography, vegetation and fire history. Berkeley uses this data to create its own wildfire hazard zones, which virtually overlap with the state's.

Defensible space regulations have been around for decades, with periodic updates motivated by fire incidents and science. The most recent update was in 2020, when the state adopted a new standard for the area extending 5 feet from the base of structures — zone zero.

Strong evidence shows buildings are especially vulnerable to embers landing in this space.

Many experts believe minimal vegetation should be allowed here, favoring hardscape such as gravel, rock or concrete. Attached wood fencing and wood patio furniture close to buildings are also in the zone zero prohibition target.

But the state Board of Forestry and Fire Protection, charged with writing the law's precise requirements, has yet to release a final draft, though it's spent years gathering input from stakeholders statewide.

As communities wait in limbo for the details on what exactly will and won't be allowed closest to their homes, many jurisdictions, including Berkeley, have started cracking down based on interpretations of existing law.

"Basically, we are more aggressive with our fuel reduction in that first 5 feet, in the eyes of the inspecting official," Arnold said.

The Scanner asked the board of forestry for an update on zone zero. Staff said they'd respond soon, but hadn't as of this posting.

Local jurisdictions such as cities can expand on CalFire defensible space regulations, but they can't reduce them.

One way Berkeley has done this is by requiring 100 feet of defensible space from structures regardless of property lines. Thick brush at the far end of a large lot, for example, may have to be thinned if it's growing close to the neighbor's house across the fence.

In Berkeley, wildfire enforcement translates to annual fire department property inspections and compliance reports and can escalate to fines or property liens.

Berkeley Fire enforcement teams still at it

Stills from a Berkeley Fire Department video on defensible space. Berkeley Fire

According to the most recent Berkeley Fire Department data, by the end of August, the city had inspected 5,092 of the 9,200 parcels subject to defensible space laws.

Of these, the department found 1,854 violations, completed 537 reinspections and resolved 566 violations. It's issued 22 citations to date.

Property owners are given 60 days to fix violations. If they aren't in compliance at the first reinspection, the owner can be fined $100 per violation.

If violations still aren't fixed at the next 30-day inspection, fines increase to $250 per day, starting from the date of the first citation, and jump to $500 per violation per day after another 30 days.

The city has some flexibility with fines, Arnold said: "We are issuing citations at the lowest possible level this year, in hopes that the process will induce compliance without the corresponding financial hardship."

Initial inspections are usually done by November, he said: "But this varies with what we find and what our staffing level is. This year, we are running a couple weeks ahead of schedule."

Last year, the city conducted 8,737 inspections and found more than 6,400 initial violations.

The fire department encourages residents to fix problems voluntarily, the city said. Fines and liens are a last resort.

No violations in Berkeley have yet reached the property lien stage, Arnold said.

A few decades ago, the concept of wildfire preparation barely touched the urban Bay Area, belonging more to forested mountain towns, with their summer lightning strikes and campfires.

Then came the deadly 1991 Oakland-Berkeley firestorm, which killed 25 people, followed by an escalating number of devastating California wildfires sweeping through entire towns — Santa Rosa, Paradise.

More than 1 million acres have already burned in wildfires throughout California this year.

Berkeley's historic 1923 fire has also come more into focus for local wildfire planners. This destructive blaze, as well as the Oakland-Berkeley firestorm, started in the hills in autumn, burning quickly downhill to denser urban areas.

Today, the city of Berkeley runs a multifaceted wildfire program called FireSafe Berkeley, which is still evolving.

The effort is funded largely through voter-approved Measure FF, an annual $8.5 million parcel tax earmarked for numerous public safety programs, including wildfire prevention.

The city also regularly pursues grants and other wildfire prevention funding.

Berkeley Fire's inspection program has been bolstered by teams of paid interns from the state fire marshal's defensible space inspector training program — up to 15 were at it this summer. Mostly young people, the interns have completed training and are getting on-the-job credit.

"They have various interests for careers, from EMS and firefighting to inspection, forestry and other interests," Arnold said.

Inspectors use a software program called Fire Aside on notebooks in the field. The app is designed for checking regulations as well as making recommendations.

Inspections are conducted from the street unless property owners give permission for a closer look.

Other city programs include free curbside chipping of plants and brush, and free green waste removal.

The city offers financial help to low-income property owners struggling to meet requirements. Yard clearing can be costly, depending on a property's size and condition.

Based on the success of last year's resident assistance pilot program, Berkeley this year received a $1 million CalFire grant to extend the support.

"Many folks will throw their name in in the hopes that they qualify, but we individually screen each application," Arnold said. The process is confidential.

"To be honest, one challenge is that many of the folks who need the help the most are difficult to reach and often aren't comfortable with digital processes," he said.

Assistance is based on the state's Housing and Community Development income thresholds.

"There are additional medical conditions or disabilities that we will consider to allow the program to be as helpful as possible to residents who need it the most," Arnold said.

Troubling eucalyptus

This summer, the city added a new element to its program: its first eucalyptus understory cleanup program, targeting the tall, highly flammable blue gum dotting Berkeley hillsides. An introduced species from Australia, eucalyptus is prolific in the Bay Area, thriving even on steep slopes.

The ambitious new effort uses city-contracted workers for a one-time clearing of eucalyptus understory on private property — the branches, leaves, peeling bark and acorns closest to the ground.

All plant understory is susceptible to sparking from embers. But the risk is especially high from oily eucalyptus.

The program, funded by up to $1 million of Measure FF money, is voluntary for property owners, who apply for the work.

In a fact sheet, the city warns that one-time clearing isn't a lasting solution.

"It's important to note that the work will not permanently remove the hazard caused by eucalyptus. The work will have to be repeated/maintained by the homeowner in the future to remain in compliance with the fire code unless the trees are voluntarily removed by the homeowner," it reads.

In a second eucalyptus project, the nonprofit Berkeley FireSafe Council, an organization primarily composed of residents in high fire hazard areas, is spearheading the voluntary removal of around 150 trees on about 20 residential properties in fire zones.

The council's main mission is preventing catastrophic wildfire.

Funded by private donations, and around $30,000 in UC Berkeley chancellor's grants, the work, currently underway, includes vegetative restoration with less fire-prone species, said Henry DeNero, FireSafe Council president.

Student volunteers from UC Berkeley's College of Natural Resources are helping.

Earlier this year, the council approached Berkeley property owners with large numbers of the trees, DeNero said.

"Twenty-nine of 30 gave us their consent," he said. "This is a huge statement of the degree to which residents understand the threat the blue gums pose."

The work encompasses tree removal and thinning. The council is increasingly shifting its focus to ecological restoration after cutting, DeNero said.

"We've sort of flipped our view to restoring a fire-safe noninvasive landscape," he said.

The council, and others including Berkeley's Disaster and Fire Safety Commission, lobbied hard for the city's new eucalyptus thinning program.

"All members of the City Council now realize how important it is to deal with our fire threats, and the blue gum eucalyptus is at the top of the list," DeNero said.

There's growing realization that a huge fire in the hills could have far-reaching impacts, he said.

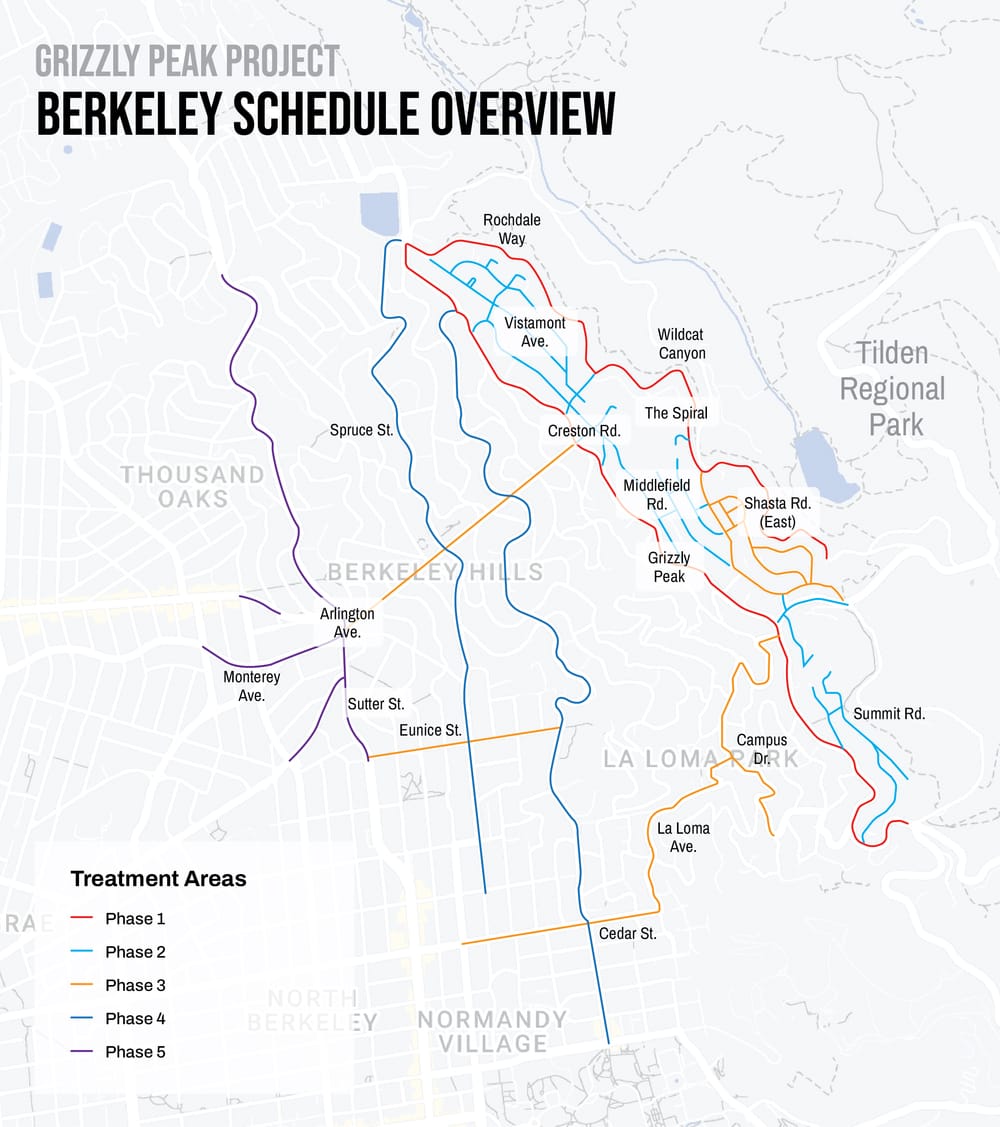

In a third eucalyptus-related project, the city is part of a major collaborative effort to cut back vegetation along Grizzly Peak Boulevard, creating a fuel break above the city, a gap in vegetation that fuels fire, while also clearing a major evacuation route.

East Bay Regional Park District is leading the project, which also includes the East Bay Municipal Utility District and UC Berkeley.

While the project area is heavy in eucalyptus, it involves clearing many kinds of plants from the sides of the road, including bamboo, juniper, cypress and grasses. The multi-year effort is funded by a $2.8 million CalFire grant.

Berkeley's eucalyptus projects, especially around homes, have some detractors.

Some people don't believe taking out trees is necessary for wildfire mitigation.

There's worry about slope stability after trees are removed. Worry about losing the carbon absorption of trees. And many people don't like the aesthetics of logging.

Indeed, eucalyptus and wildfire have a long history of debate, including in the Bay Area.

And while defensible space is required in high fire hazard areas, there's no law, state or local, requiring the removal of eucalyptus or any plant species.

But today, many fire experts strongly advocate for reducing the eucalyptus fire fuel load in high-hazard areas. How best to do this, and to what degree, is controversial.

But few disagree that the towering trees with a distinct camphor smell can be torches to fire.

Berkeley wildfire prevention work is getting nods

For the past two years, Berkeley has earned the Fire Risk Reduction Community distinction from the state Board of Forestry, in recognition for its wildfire prevention efforts.

This year it was one of just 11 cities statewide to make the list. Most recipients are fire protection districts, which tend to serve large rural areas, along with some counties as well as park and utility districts.

According to the legislation enacting the program, fire risk reduction communities are "local agencies located in a state responsibility area or a very high fire hazard severity zone… that meet best practices for local fire planning."

The East Bay Regional Park District and East Bay Municipal Utility District also made the 2024 list.

The Park District is reducing catastrophic wildfires before they occur. 30 dedicated fire personnel are actively engaged in pile-burning operations with @AlamedaCoFire in Claremont Canyon in the Oakland Hills. #WildfirePrevention #FuelsManagement #CommunitySafety #LoveEBRPD pic.twitter.com/O6AsC7ELgT

— East Bay Regional Park District (@EBRPD) April 11, 2024

Arnold points out that one advantage of the Fire Risk Reduction Community status is that insurance companies, embroiled in the crisis of pulling back from California coverage because of the state's wildfire vulnerability, look favorably at larger-scale prevention efforts.

"It's important to note that this is another great opportunity to shore up insurability, but not a guarantee," Arnold said. "Mitigation of hazards at scale, regionally, is the best bet for insurers being interested in continuing coverage in the market."

In a similar vein, Berkeley is now home to nine Firewise communities, a voluntary certification program of the National Fire Protection Association that encourages wildfire-vulnerable neighborhoods to take steps to reduce risks such as maintaining defensible space, installing fire-resistant roofs, covering vents with wire mesh to block embers — and more.

The number of East Bay Firewise communities is steadily growing. Some insurers say this can help reduce premium costs.

But assessing the overall impact of these discounts isn't easy as insurance companies keep their data private, and set rates on a case-by-case basis.

Details are also scarce on the impact of a 2022 state law requiring insurers to discount rates for property owners who take strict wildfire mitigation steps, referred to as Safer From Wildfires, on their houses and yards. The standard is endorsed heavily by insurance companies.

Safer from Wildfires mirrors a program of the Insurance Institute for Business and Home Safety, a nonprofit research group that advises insurers. The institute calls its program Wildfire Prepared Homes, and it certifies property owners who meet this standard. Some insurers factor this in when setting rates.

In a local twist, last year UC Berkeley teamed with the insurance institute and CSAA insurance, the provider of AAA insurance, on a wildfire-resilient home design competition for students. Kristina Hill, director of the university's Institute for Urban and Regional Development, administered the contest.

"While a changing climate may increase our wildfire threat, these award-winning designs illuminate that the visual draw and practical function of a home can go hand in hand," Hill said on the competition website.

"The top designs addressed varying budget levels (low, medium, high) and in addition to establishing a completely noncombustible home ignition zone — which focuses on placing soils and hardscape rather than vegetation around a home's perimeter — emphasize removing flammable mulch, yard debris, trees and bushes," said Alister Watt, the institute's chief product officer.

DeNero said he's hearing positive responses to the city's fire prevention efforts.

"City officials in numerous departments are 'on-board' in addressing the fire threat and doing what they can in their division. And virtually all of the residents we talk with want to reduce hazardous material [fire-prone vegetation] that could cause harm to their homes and the city," DeNero said.

"Although there are the expected occasional complaints about BFD's residential inspection process, it is widely supported by residents. There is also heavy use of the new curbside chipper program that allows residents to schedule 'on demand' chipping and removal of debris," DeNero said.

"The primary challenge we face is that, in our opinion, things are still not moving with sufficient urgency," DeNero said, speaking of all efforts to reduce Berkeley's susceptibility to major wildfire.

To be sure, cutting down or thinning any plant, from flower to towering tree, can be highly sensitive, wildfire experts acknowledge. This is especially true for landscaping that's been planted and cared for by residents, sometimes for decades.

"One of the challenges is linking the work that we ask people to do to the impact that it can have on safety; the problem seems intractably large, and it's difficult to see for an individual how their actions have an effect," Arnold said.

"But multiply that by 8,000 residents, and suddenly you have an army attacking the challenge," he said, "and that really matters."

- Defensible space inspections

- Wildfire risks in Berkeley

- How to create defensible space and harden your home

- BFD's free chipper service

- Paid internship opportunities

- More city resources on wildfire preparedness

Kate Darby Rauch spent more than 10 years as a daily news reporter with the East Bay Times and has freelanced for numerous publications, including the Washington Post, Newsday, the Seattle Times, San Francisco Chronicle and Oakland Magazine.