A near-fatal bike crash may shift how Berkeley does street design

In 2016, a driver rear-ended Mike Wilson’s wife while she was biking home from work at UC Berkeley. The crash was "100% preventable," Wilson said.

By Kate Darby Rauch

In a challenge to the way cities usually do business, Berkeley’s new Street Trauma Prevention program is moving from a daring idea to reality.

The initiative, which looks to be a nationwide first, creates a new position in the Berkeley Fire Department that seeks to reduce bike and pedestrian collisions through street design – a job usually done exclusively by traffic engineers in the Public Works department.

"It’s groundbreaking," said Mike Wilson, a former firefighter who is on the city’s Disaster and Fire Safety Commission.

"The mission of the fire service has expanded to consider the overall safety of the city," he said, going beyond emergency response. "It’s a prevention lens. It’s brand new for the fire service [as far as street trauma], but it’s also very much aligned with what they’ve done for 50 years around fire safety."

In June, the Berkeley City Council approved $265,000 in new fire department funding for a Street Trauma Prevention program manager.

The job description is now being finalized and the hiring process could start this fall.

"A street design problem" caused fateful crash

Left: Meg Schwarzman with 11-month-old son Oliver the month before the crash that nearly killed her. Right: Schwarzman recovering at Highland Hospital after the crash. Mike Wilson

Mike Wilson’s personal story is largely credited with powering the new concept.

In 2016, a driver violently rear-ended Wilson’s wife on Fulton Street at Bancroft Way while she was biking home from work at UC Berkeley.

Dragged under the car for 60 feet, Meg Schwarzman suffered severe injuries including a lacerated liver, collapsed lung, broken ribs, multiple pelvic fractures, a broken collarbone and broken facial bones, along with extreme blood loss.

Firefighters said she came within minutes of losing her life.

The collision was "100% preventable," Wilson said. "This was a street design problem."

Read more about traffic safety in Berkeley.

Immediately after the crash, the couple’s focus was intently on healing, Wilson said, and caring for their 11-month-old son.

Schwarzman "had a long physical recovery and a long psychological recovery," he said.

But as she improved, their thoughts increasingly went to making a difference.

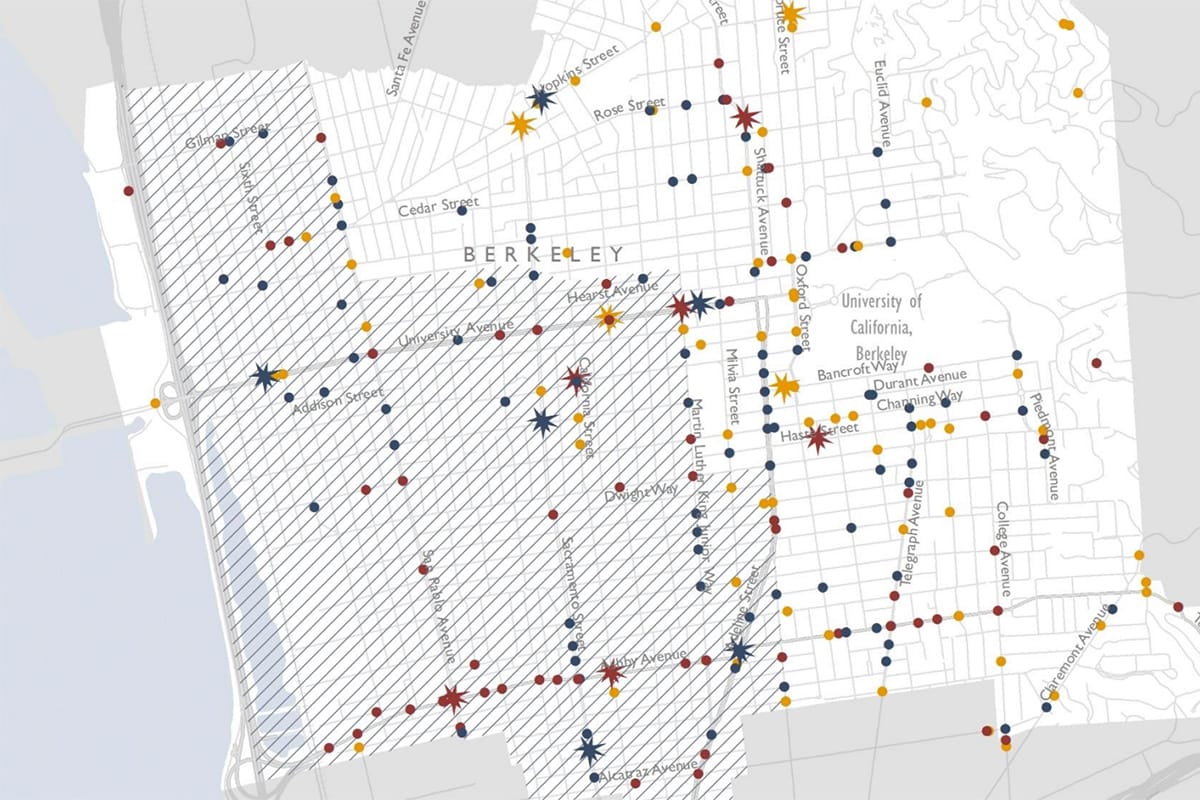

Wilson said he became "hugely motivated" to get involved in Berkeley’s efforts to reduce bike and pedestrian collisions as part of Vision Zero, the city’s 2019 plan, based on a national model, to "eliminate traffic deaths and severe injuries by 2028."

Looking south at Bancroft Way and Fulton Street where the bike lane Meg Schwarzman was using in 2016 abruptly ends. Mike Wilson

After being appointed to the Disaster and Fire Safety Commission last year, Wilson’s mind churned with observations from his 13 years as a firefighter, paramedic and EMT in Salinas and Santa Cruz County before he moved to Berkeley in 1996 to attend graduate school in public health.

Today Wilson works as a safety engineer for the state Division of Occupational Safety and Health (Cal/OSHA): a job, he said, that also feeds his interest in preventing serious collisions.

Conversations, meetings and huddles later, the vision for the new Street Trauma Prevention program began taking shape. Along with the name.

(Not to be confused with Berkeley’s nearly 1-year-old Specialized Care Unit, which fields mental health and substance use crisis calls.)

It quickly became clear to Wilson that setting the street trauma program within the fire service made sense: Who better to help design safer streets than the very people who render aid to crash victims?

Crucially, the Berkeley Fire Department was on board and helped build the idea, as did bicycling advocates from Walk Bike Berkeley.

"I hope we can be a part of helping to turn what, quite frankly, has been an incredibly divisive issue for our community into something that the majority of residents and our responders can unify behind," Berkeley Fire Chief Dave Sprague said.

Divisive because, historically, fire officials have been understandably wary of or against street design changes for fear they’ll slow response times.

This includes commonly used mitigations to slow traffic, such as intersection bulb-outs or curb extensions that narrow street width; chicanes or curb offsets that turn straight-aways into curvy narrow roadways; and reduced speeds, speed humps and more.

Street safety projects, emergency response times don't need to be at odds, research says

Engineered traffic safety solutions: A new speed bump on Deakin Street in Oakland near the Berkeley border (left) and a solid bike-lane protective device at Berkeley High (right). Mike Wilson

The thinking is shifting, Sprague said, because a growing body of research has shown that, with careful planning, improved emergency response times can go hand-in-hand with street safety mitigations.

"I am absolutely convinced that there is a way that we can achieve the results of Street Trauma Prevention and maintain response times that meet the communities’ expectations," Sprague said, adding that he hadn’t heard any grumbling from the ranks about the plan.

The program will start with one position, a manager, tasked with bringing a fire department perspective, including data and research, to transportation planning.

That means working side-by-side with Public Works, Sprague said.

Recent traffic safety improvements at Bancroft Way and Fulton Street. Kate Darby Rauch

He views the program as a potential bridge between departments and local stakeholders, such as researchers, inventors, designers, businesses and advocates, who will develop novel approaches to transportation design that both "reduce injuries and deaths and allow responders to get on scene quickly and begin firefighting or emergency medical interventions," Sprague said.

Among other duties, Sprague said, the new Street Trauma Prevention manager will be tasked with researching ways to slow traffic in high-injury areas without "gravely impacting" emergency response times.

As a responder himself, Sprague appreciates the critical importance of getting it right.

"It can be very traumatic to be responsible for someone’s life, quite literally, and know that it is taking more time to get them to definitive care because of direct or indirect impacts from transportation design," he said. "These experiences represent the real other half of the Street Trauma Prevention story that needs to be better articulated by the fire service."

He said it’s all about "passionate people trying to do the right thing, and real issues [that still] need to be solved" involving Vision Zero, transportation planning and emergency responders.

"It shouldn’t take catastrophes to prompt these measures"

Wilson, as a former firefighter, also intimately gets this challenge.

His wife was hit where the Fulton Street bike lane ended, sending cyclists into the regular flow of traffic. Today, she’s back on a bike again, but she won’t pedal on city streets.

Fulton Street now has a dedicated bike lane – the city’s response to the horrific near-death ordeal.

It shouldn’t take catastrophes to prompt these measures, Wilson said. But it’s also not that simple.

His wife’s life was saved by firefighters because they got to her within 2 minutes of getting hit. At the same time, a protected bike lane, with physical barriers to help block veering cars, could have buffered that hit.

"If your perspective only has to do with how quickly you can get to an incident and how quickly you can transfer that person to Highland Hospital then any of those improvements look like an impediment," Wilson said.

Follow the data, follow the evidence for win-win measures, which do exist, emphasize Wilson, Sprague and other experts.

Fast emergency response times and safer streets for walkers and bikers aren’t mutually exclusive, they say.

- Safety is the highest priority.

- Traffic deaths and severe injuries are preventable and unacceptable.

- People make mistakes.

- Slower streets are safer streets.

- Supporters pledge to create safer transportation options for people who walk, bike and take transit.

- Street safety must be achieved equitably.

- Vision Zero will be accountable, transparent and data-driven.

All of this has long been the purview of city traffic engineers and planners, including in Berkeley, highlighted today under Vision Zero and evidenced by the growing number of protected bike lanes springing up across the city.

This work is also fundamental to the city’s Complete Streets Policy, required by state law, which, calls for "a comprehensive, integrated transportation network with infrastructure and design that allows safe and convenient travel along and across streets for all users, including pedestrians, bicyclists, persons with disabilities, motorists, movers of commercial goods, users and operators of public transportation, emergency vehicles, seniors, children, youth, and families," according to the 2012 City Council resolution approving it.

Vision Zero and Complete Streets are now joined at the hip in transportation planning. Both respond to efforts to encourage cleaner modes of transportation such as biking and walking.

The new Street Trauma Prevention program isn’t intended to duplicate or compete with that work but to forge a partnership that adds unique fire department insights, Sprague and Wilson said.

BFD qualms stalled Hopkins project, advocates say

"The fire department really needs to have in-house expertise to design streets for safety … so they can effectively engage with Public Works," said Ben Gerhardstein of Walk Bike Berkeley, emphasizing this includes bringing effective emergency response to the planning table.

A longstanding requirement of any new street construction project in Berkeley is fire department approval to make sure designs meet fire codes.

The lack of this approval is cited as why the contentious, years-long planning process to add dedicated bike lanes to Hopkins Street was scrapped in 2023. Pulled or postponed depends on who you ask.

The project pitted bike safety advocates against people concerned about the loss of street parking in a popular neighborhood shopping area in northwest Berkeley.

Backers of the Street Trauma Prevention program think the Hopkins issue could have been far less bumpy if the fire department had been involved at the get-go in design, as a planning partner.

This was one genesis for launching the street trauma program, they said.

"[Hopkins] underscored the need for us to engage with the fire department and make sure our fire department understood our Vision Zero goals for the city — and that we have shared buy-in across city departments," Gerhardstein said.

The fire department has now expressed strong support for this shared goal, he added.

Speaking in general terms, Sprague said: "It’s a situation where there can be better alignment around common goals than there has been historically."

Mike Wilson: "You’re going to see this spread"

Seung Lee, a city spokesman, recently indicated that the city manager’s office and Public Works department also welcome the new program within Berkeley Fire.

"We look forward to collaborating to advance our Vision Zero goals," he said. (The Vision Zero program, which has languished, may be getting a new boost itself in the coming year: The city has just posted a job announcement for a new planner to spearhead that effort.)

Another lure for a street trauma prevention approach, according to Wilson, Sprague and Gerhardstein, is involving first responders in solutions that reduce their exposure to often grisly, sad and deeply affecting calls.

"There are long-term effects of continuous exposure to trauma among firefighters and paramedics," Wilson said. "It’s a real thing."

"There’s an element here that’s important in protecting the mental health of our workforce," said Gerhardstein.

In trying the new program, the city appears a pioneer. It will be closely watched, Wilson predicts.

"Berkeley is kind of putting a flag out in front," he said."You’re going to see this spread to other cities."

- On average, nearly 700 people are hurt, and five are killed, in collisions in Berkeley each year

- From 2017-2022, street trauma resulted in injuries to 490 people in vehicles, 103 people on bikes and 101 pedestrians on average each year.

- Over that period, there were no deaths and an average of two people injured each year in Berkeley fires, "a testament" to BFD’s effectiveness in fire prevention and response.

- Collisions involving someone riding a bike or walking in Berkeley make up about 61% of the city's serious or fatal collisions — despite making up just 40% of its trips

- Drivers operating at unsafe speeds and failing to yield at crosswalks are the two most common causes of severe and fatal collisions in Berkeley, amounting to 33% of such incidents from 2011-2020.

- While 71% of Berkeley residents say they would like to rely on bicycles for daily use, most don't feel safe enough to do so, the city has found.

Kate Darby Rauch spent more than 10 years as a daily news reporter with the East Bay Times and has freelanced for numerous publications, including the Washington Post, Newsday, the Seattle Times, San Francisco Chronicle and Oakland Magazine.

Read more about Meg Schwarzman's recovery

Scanner founder Emilie Raguso was honored to cover Meg Schwarzman's recovery at some length on Berkeleyside in 2016.