The Gene Ransom I knew: More than a basketball player

Ransom's former partner, Paula Gerstenblatt, wrote this remembrance in 2022. TBS has published it along with an update about the case.

By Paula Gerstenblatt

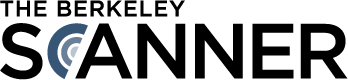

Gene Ransom was my partner for 20 years. I met Gene at Berkeley High — not during his glory playing days, rather as my son’s coach in his first season coaching the freshman boys basketball team.

I grew up in New England so I had no idea who Gene the Dream was or his legendary basketball career at Berkeley High School and Cal.

When my son’s former PAL coach said Gene was one of the greatest athletes to come out of Northern California, I laughed, "You mean that short guy coaching my son?"

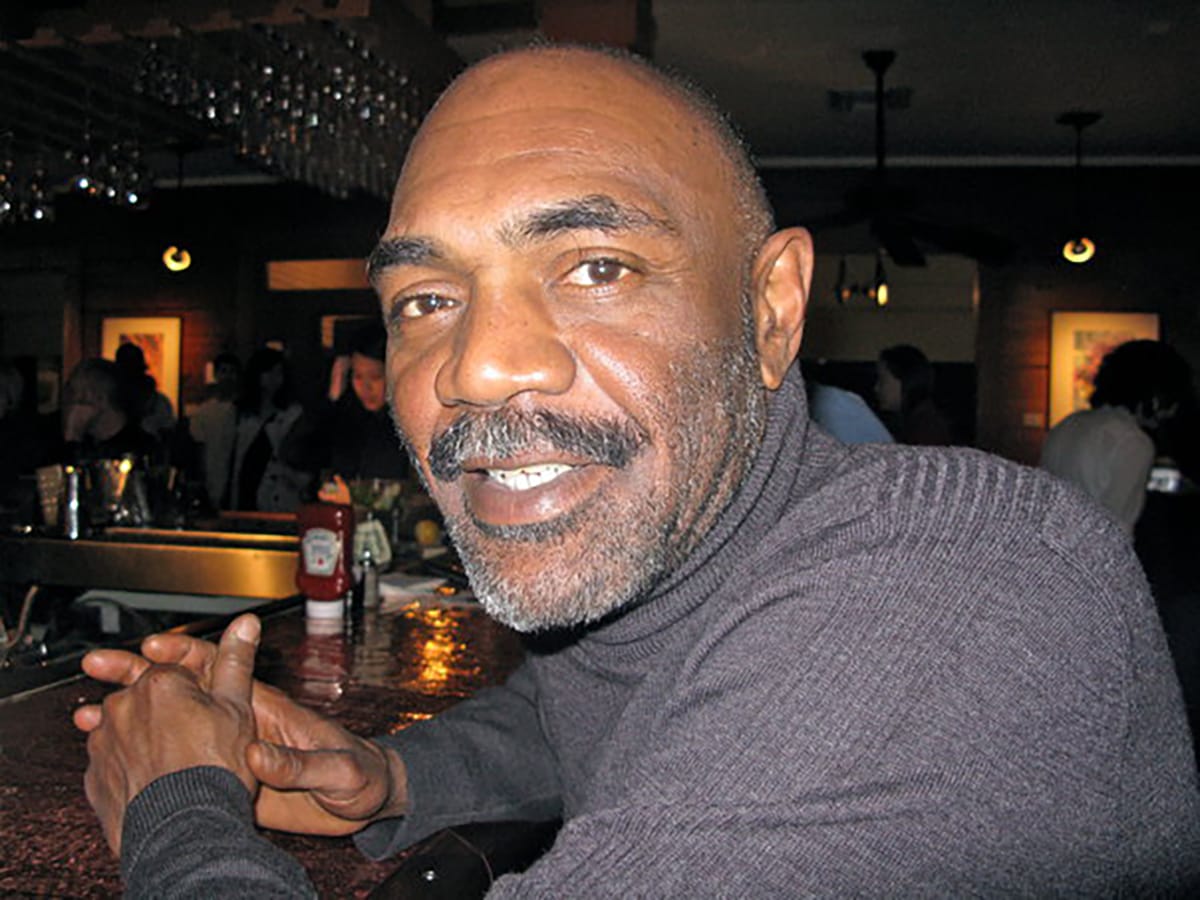

I would soon learn how Gene’s magical moves on the court secured his place in hoops history, as well as constrain him in a box based on eight years of his life.

Author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie warns that if we hear only a single story about another person or country, we risk a critical misunderstanding. While trying to absorb the shocking and brutal death of a man I loved deeply, the accolades of his athletic genius poured in.

News outlets nationally, and even globally, picked up the story of the tragic shooting of a former Cal basketball star.

I understand, I do, but my memories of Gene extend far beyond the basketball court. While his basketball career made Gene a legend, it is a single story that omits the complex character born in Caruthers, California, as part of the Great Migration from Texas, raised in the country chasing chickens, and at 5 years old moved to Oakland and later Berkeley where his parents bought a house on Curtis Street.

Gene attended Berkeley public schools where he played sports in recreation programs, Little League coached by his dad "Handsome Ransom," and excelled as a multi-sport athlete on school teams.

He was driven and passionate, and while his talents may have been natural to an extent, he worked hard. He lived near the West Campus gym and spent hours practicing alone; dribbling between chairs, shooting and conjuring images of the greats he intended not just to live up to, but exceed.

He could be found on the outdoor courts of Berkeley and Oakland playing pickup games in epic battles. He loved basketball, and though he often told me he was a better baseball player, he rejected a lucrative pro offer out of high school in favor of a scholarship at Cal.

When I met Gene, he was thrilled to be back in the game as a coach. He loved working with young people and supporting their development. In the 1990s, he worked with Doug Harris and Athletes United for Peace, a nonprofit committed to promoting peace, education and friendship, often through sports.

Gene was more than a coach though, he was a teacher. His method did not include being punitive or demeaning. When he took a player out of the game he put his arm around his shoulder, leaned in closely and offered "options."

When telling a player to go lower in a defense position, he took his hand and pressed the player’s back to show how low, because he knew his players had varying learning styles and not all were auditory learners.

His dedication and love were felt by all his players and they returned it in kind.

Gene’s humor was another ingredient of his teaching style, creating nicknames for all the players, which were quickly adopted, and soon everyone referred to themselves and each other by their designated name.

Gene’s greatness was admired, but it was also a threat. He sat a lot of senior players down during his high school and college career. He was drafted by the Warriors when Magic Johnson entered pro basketball as a point guard.

Warriors Coach Al Attles asked Gene how he was going to guard Magic, and Gene’s response was how was Magic going to guard him.

Eventually he was released by the Warriors and tried out for another pro team but essentially his basketball career ended. He played a few years in minor league baseball before calling it quits as a professional athlete.

It is not a secret Gene struggled after his career was over, a familiar narrative for many players. He spoke candidly to me about those years, the searching for an identity outside of sports and trying to find his way in a world that defined him by his five-overtime record and his no-look passes.

He told me the "struggling" Gene was more palatable, no longer a threat. The "haters" who took their place on the bench or never made it to the bench, could take some small satisfaction, or worse pity, in his struggles. He felt this acutely, and it pained him.

Gene left the Bay Area for several years to sort out his life outside of the microscope. He returned in 1999 to Berkeley and his first love, basketball, this time as a coach at his alma mater.

What Gene experienced as a high school coach mirrored his experience as a player. His coaching excellence was the new threat, and while he should have been promoted or sought after by every high school and even college, that was not the case.

Gene was gaining notoriety as a winning coach, beloved by his players and their families, and feeling fulfilled. We met and fell in love, and he was thriving.

However, I saw firsthand the dynamic he described during and after his basketball career, though in this iteration it blunted his coaching aspirations.

When the head coach position opened up at Berkeley High, an outsider who knew nothing about Berkeley and lacked Gene’s credentials was given the job. Gene stayed on another year and then left.

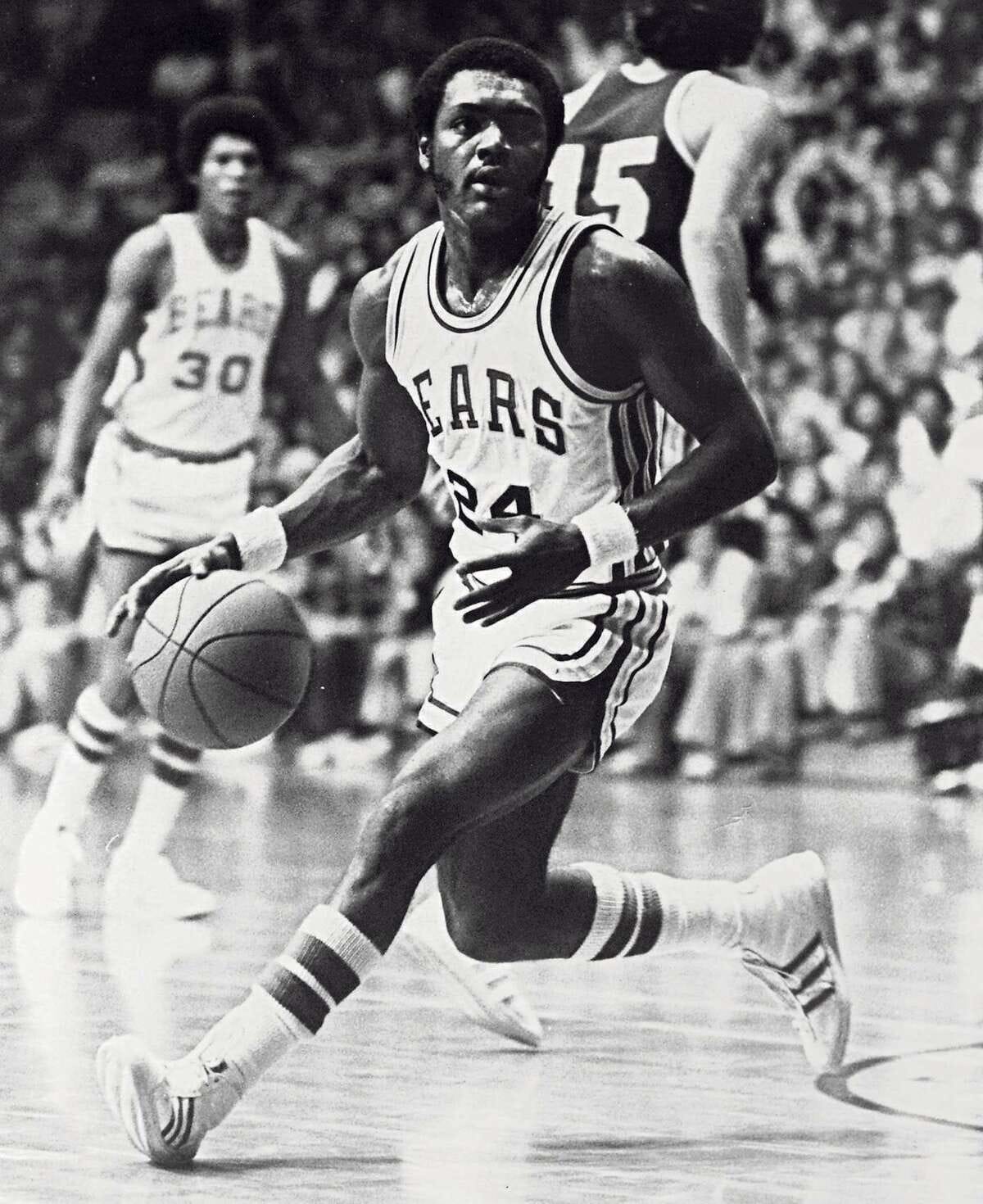

Gene’s former players asked him to start an AAU travel team, which is how Reach Your Goals (RYG) was born.

Gene and I decided the team had to be more than basketball and included a required academic and community service component.

Our players were often overlooked by elite teams. They came from all over the Bay Area: Richmond, Freemont, Novato, Pinole, Berkeley and beyond.

We were the Bad News Bears of AAU basketball. At our first tournament in Reno, we took home the second-place trophy and our success continued, but not only in the form of winning games.

Gene told the players that through this team they would form lifelong friendships, and even if they didn’t see each other for 10 years, they would instantly rekindle their relationship.

We stayed in rented houses, not hotels, spending time discussing the assigned book, cooking together and talking into the night. It was a magical two years, which ended with most of the players going to college with or without a basketball scholarship, and growing into fine young men.

When news of Gene’s death spread, I received calls from former RYG players and their parents, and they reached out to each other from all parts of the country and globe sharing stories and their grief.

Gene was right, the treasured outcome of the team was not trophies, rather a lifelong bond.

In 2001, I answered the phone at our home in Pinole. The caller was from the Athletic Department at Cal looking for Gene. They wanted to induct him into the Hall of Fame.

Gene was taken aback and, while he was flattered and proud, it brought back conflicting memories of a high and low point in his life.

Despite an illustrious basketball career and packing the gym, Gene never graduated from Cal.

Gene spoke out about player exploitation and racism before it was popular, he refused to take what he called a "dummy" English class and, after three years, Cal and Gene parted ways and it was not amicable.

Gene went to the University of Nevada, Reno, for a year, where he played but didn’t graduate.

Gene accepted the Hall of Fame invitation. We spent hours talking about his speech, what he wanted to say and why. There was a lingering bitterness he longed to heal; however, authenticity was equally important.

In his speech, he described hearing the cannons go off at Cal football games as a child and vowed one day to play for Cal.

He had a shoebox full of letters from schools all over the country offering him a scholarship; however, he chose Cal.

Through his individual narrative, he told a collective story of the exploitation of athletes and the racism that permeated college athletics.

People in the audience were captivated, and you could hear a pin drop as he talked. He broke down a few times to collect himself, as Gene was emotional and prone to tears.

It brought him full circle, and the fact he was completing his degree at New College of California and graduated shortly after, was a celebration of a longer academic journey and personal redemption.

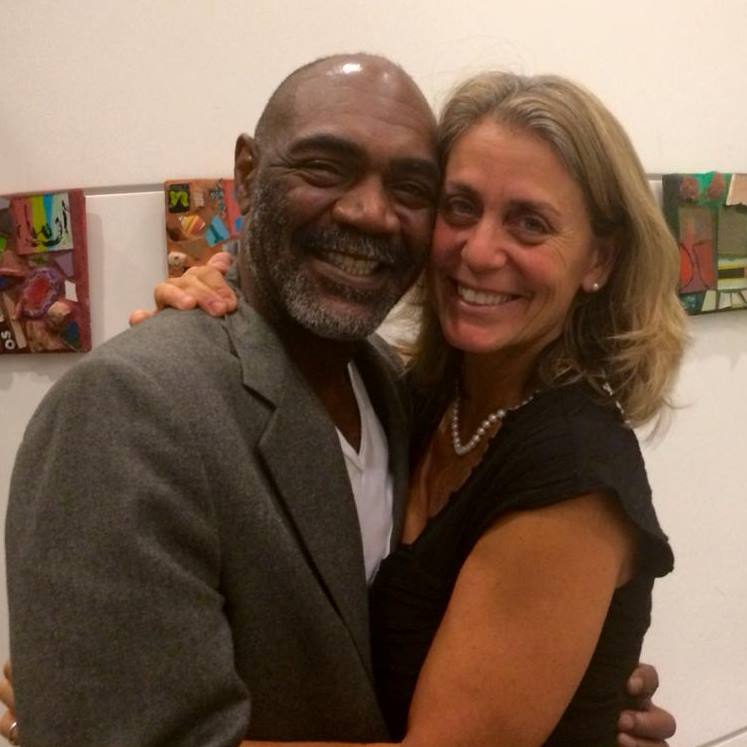

Left: feeding the pack. Right: Gene and Paula. Paula Gerstenblatt

Following his basketball career, Gene became a professional house painter and, like everything else he did, he painted to perfection.

He worked seasonally for the post office and other jobs, but his pot of gold at the end of the rainbow was becoming a longshoreman like his father, and eventually his turn came up.

On the waterfront, Gene’s reputation as a player and son of "Handsome" Ransom preceded him; however, he became known as a hard worker and for his gregarious personality.

Gene obtained his A Book, which is the highest rank of longshoreman, achieving financial security and respect from his co-workers.

And still he found time to mentor players, attend their games and show a sincere interest in their athletic and personal development.

Gene, like most of us, was a complex human being.

He was father to Thaxter, stepdad to my children Rena and Jonathan Davis, co-parent to our pack of four dogs, son and brother, mentor to his players and beloved friend to many.

There is a temptation to reduce a life to a single story chartered by accomplishments, material gain or even mistakes. I loved the man and spent 20 years of my life with him, so I know his story from the inside out.

He aspired to become his best self for those he loved. Sometimes that goes well and other times not; however, redemptive and transformative learning involves valleys as well as peaks.

Gene had personality plus. He loved our four dogs like our children and was happiest at home or spending the day at Stinson Beach.

When I moved to Austin, Texas, for my PhD, and later to Portland, Maine, to become a professor, he loved coming to visit where he was just "Gene," and adored for the person he was outside of basketball.

He was generous and charming, and when he made someone smile — stranger or friend — he would say "I’ve done my job."

In this time of deep grief, retrieving those smiles feels hard pressed through the tears and sadness. The way he died adds salt to an open wound.

Though Gene and I parted a few years ago, his words echo in my head, his smile greets me, and the love and life we shared lives on in my heart and memories.

Gene anticipated a single story in the event of his death, and made me promise to counter the narrative with a truthful, more complete picture of Gene Ransom and to "keep it real."

So many of us are missing him, angered by the brutality of his death, and wishing we could see him one last time. Gene was many things to many people, but one thing is for sure, he was more than a basketball player.