In split vote, Berkeley approves license plate readers for police

Berkeley police hope to roll out the new license plate reader program in the fall. Locations have not been chosen but will be public when they are.

A City Council majority voted Tuesday night to let Berkeley police use automated license plate readers in their efforts to fight crime.

Some community members, including the Police Accountability Board, came out in strong opposition to the proposal, citing concerns about civil liberties and a lack of data showing the readers to be effective.

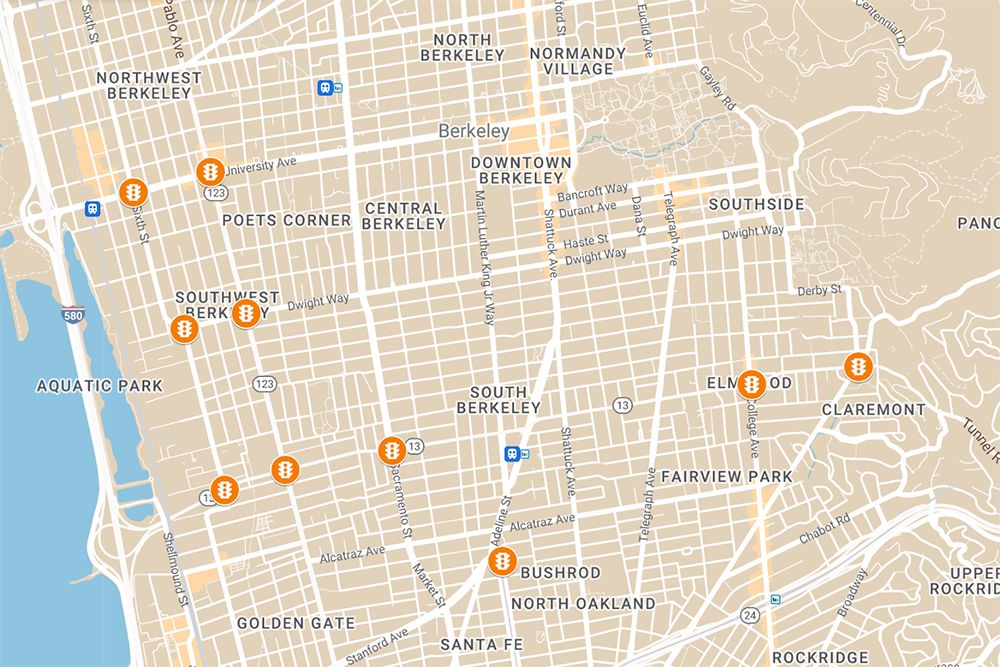

But, in the end, most city officials said the policy addressed many of the concerns and will be limited to a two-year pilot with 52 readers mounted around the city.

"In an ideal world, crime-fighting technologies would be obsolete," said Councilman Terry Taplin, who brought the item forward for consideration years ago. Unfortunately, he added, the world remains imperfect, "which does not enable us to disregard the safety concerns of our residents, nor does it excuse us from the responsibility to pursue common-sense solutions to combat auto-related crimes."

Ultimately, the Berkeley police proposal passed easily: Taplin voted in favor, along with colleagues Rashi Kesarwani, Mark Humbert, Susan Wengraf, Rigel Robinson and Mayor Jesse Arreguín.

Councilman Ben Bartlett was the lone no vote, while Councilwoman Sophie Hahn abstained. Councilwoman Kate Harrison was absent due to illness.

The Berkeley Police Department hopes to roll out the new program in the fall.

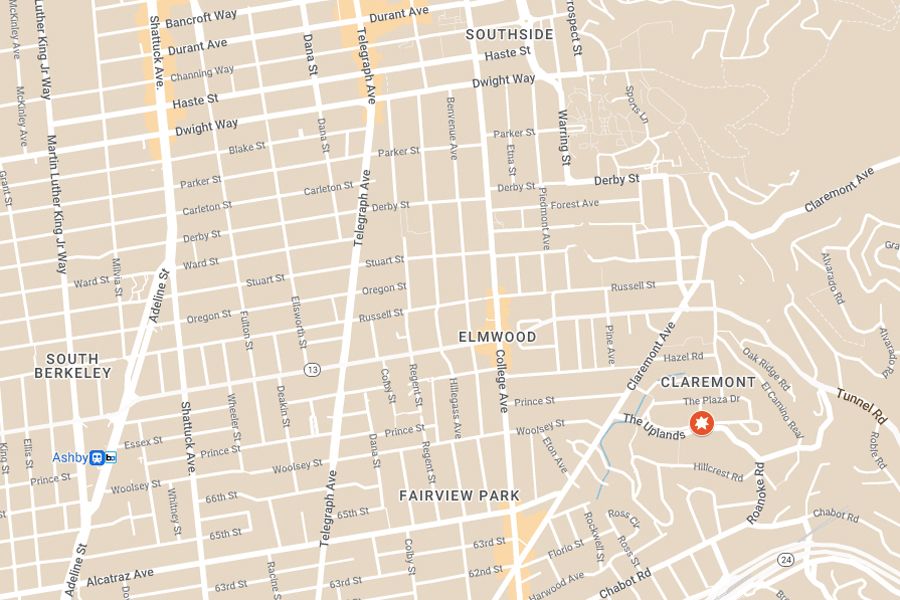

Now that city officials have signed off, BPD will work to choose a vendor who will help determine reader locations. Those locations will be public once they are selected, police said.

Berkeley police are separately working to launch a new security camera program at 10 intersections around the city which will be used to investigate crime and serious traffic collisions.

Unlike the surveillance cameras, police said, the automated license plate readers — called ALPRs for short — will capture only vehicles and license plates.

They will not capture images of people and police say, in nearly all cases, officers will need to vet any "hits" they get — for stolen cars or other wanted vehicles — before taking any law enforcement action.

Berkeley police also plan to use the license plate readers in response to statewide alerts for missing children and at-risk elders.

During public comment, community members expressed strong views about the program, with some calling it a "boondoggle" and describing it as "snake oil."

Others pointed out that license plates are routinely scanned around the Bay Area already and that police need modern tools to help protect the community.

Calling in on Zoom, longtime Berkeley resident Toni Mester said the comments seemed to boil down to attitudes about police, with those who support law enforcement in favor of ALPRs and those critical of police in opposition.

"Every tool can be a weapon," Mester said. "It depends on the intent of the user."

Berkeley officials and police committed to collecting robust data to help see how well the license plate readers work in the city in the coming years.

While most officials expressed support for the ALPR program, Councilwoman Hahn said she had "serious concerns" about the number of readers that would be mounted around the city and how intrusive they might be.

Councilman Bartlett said he could not support the program for Berkeley police given this past year's text scandal, particularly because the sergeant who was most implicated in the offensive texts has recently returned to work.

Bartlett repeatedly referred to that officer as "Sgt. Hate" and described BPD as a "problematic department."

A number of community members who commented Tuesday night, on the ALPR item and at other points in the evening, also referenced the text scandal and expressed frustration at the outcome and process this past week.

But the most consistent theme throughout the night, from officials and public speakers alike, was a concern about rising crime and public safety.

Many crimes in Berkeley are up this year, with vehicle theft up nearly 70%, burglary up 20% and robbery up nearly 10% compared to the same period in 2022.

More than 750 vehicles have been stolen in Berkeley this year, which is an average of nearly four cars a day, according to the latest department data.

Carjacking, while much less common, has also spiked in Berkeley this year.

There were 15 carjacking reports in the first half of the year alone. From 2018 to 2022, Berkeley averaged about 13 reports a year, according to BPD data.

When it was her time to speak, Councilwoman Kesarwani said the city attorney's office had already vetted the proposed ALPR policy to address legal concerns.

She said she saw the readers as a useful addition to law enforcement in Berkeley — particularly given the ongoing staffing crunch.

BPD is authorized to hire 181 officers but has just 123 available for full duty as of this week due to injuries, training and leave.

Kesarwani also noted that Albany and Berkeley were the only cities left in Alameda County that did not allow their police to use automated license plate readers. And she said it was time for that to change.

"We want our police department to have the tools to bring accountability for these violent and property crimes," she said.